Organizational Learning and Experimentation

Learn as an Organization

In a business context, learning means transforming new information into new skills, behaviors, and actions. Organizations “learn” in the sense that they modify how they get the job done to reflect new ideas, knowledge, and feedback: how to produce or launch a product more efficiently, how to install new equipment, what the competition is up to, and so on. Learning involves improvement and change.

It should be pretty obvious that learning is important to an organization’s health and long life. Yet, despite larger and larger investments in education and training, many companies (and managements) still fail to make tangible progress. Some managers don’t see much need for further learning. They’ve got work to do and little enough time to do it. Others see real value in learning, but they, too, feel overloaded with meetings, deadlines, and other work. Still, others feel that learning is too much work and aren’t convinced of the payoff. It seems easier and safer to keep doing what already works. Here’s Professor Linda Hill from Harvard Business School on why it’s easy for people to neglect learning:

I think what makes all of this very hard is that if you've been successful and things have worked for you, you don't necessarily know what aspects of what you've been doing have been working for you and which ones have been holding you back unless you have been introspective and reflected on why has it worked. We tend to stop and reflect only when we have a misstep or make a mistake, which is why stars can have more trouble learning to lead because they actually haven't stopped to reflect on why they were even successful as stars or whatever has gone on. So then, when they go to try to help other people, they have some misconceptions about why they were successful. So I think that what's hard about it is that if it's working for you — we're all busy. There's just lots to do. We just don't bother. We don't take the time to reflect, and once we do stop to reflect, it's going to take us a while to work that out. And the other piece of it is it's about unlearning. You know good and well what you need to be doing, right? But that means you have to unlearn what you used to be doing, and that is very hard. The problem is, you have to do the right thing poorly before you can do the right thing right. So your performance actually goes down before it gets better.

Many of your employees carry these mixed feelings about individual learning. That's important in two regards — first, it can impede their own growth; second, it changes the way that managers see processes and create a spirit of learning in their organization itself. Many managers, for example, see organizational learning as simply an aggregation of the individual learning undertaken by its members. Failure to learn is most obvious when an organization repeats the same mistakes, or key individuals leave and their knowledge goes out the door with them.

The Myths of Organizational Learning

Our first step will be—as it has been in Decision-making Management and Implementation Management—to debunk some myths.

Most organizational learning takes place in the classroom during formal workshops, training, or seminars: Companies invest a lot of resources in terms of formal learning, but in reality, most learning takes place on the job. This is true for both individual learning and organizational learning. Individuals learn by doing and gain experience and confidence through action; companies learn by having repeatable processes that are measured, evaluated, and improved through deliberate effort. Today’s pace of change is so rapid that managers (and organizations) have to commit to both informal, on-the-fly learning and to formal approaches (like AARs) if they don’t want to be left behind. Most organizational and managerial learning occurs via three main channels:

Reflection (reviewing past experiences)

Intelligence gathering (collecting information about the environment)

Experimentation (trying new approaches)

Organizational learning does not necessarily require changes in behavior: We observed some of the benefits of organizational learning with Fuerte Construction. We also saw how difficult it is to change behavior. For our purposes, learning has not taken place unless behavior has changed. In an organizational and managerial setting, simply possessing useful information is not enough. All too often, managers interpret new knowledge in terms of what they already know (or think they know), short-circuiting the learning process. There’s a saying that, “unfortunately, most managers who’ve had 30 years’ experience have been having the same experience for 30 years.”

Organizing and contributing to an organization's learning agenda is the responsibility of specific managers such as a Chief Learning Officer or the Human Resources department: It's critical to not conflate individual learning, process learning, and organizational learning. Anybody who is involved in the process benefits from the on-the-job learning that Professor Edmondson talked about earlier, and individuals directly involved in those processes have a unique perspective. When someone feels they have learned something important, it is vital that they bring that forward. Learning cannot solely be the responsibility of only a few. Beyond that, any individual in an organization should have a personal learning agenda and set learning goals that not only assist the organization but create future outcomes for that individual.

Before we start, we first need to get rid of the idea that people are analogous to sponges. The common idea that people will absorb, to an extent, any information presented to them is incompatible with scientists’ understanding of how the human brain actually takes in, processes, and uses information. First, humans have limited attention and memory, particularly in an action-packed professional environment, so simply telling someone something is often not enough—as most parents are well aware. Even if the information is absorbed, the mind still has to process it correctly—and there are many ways for that to go wrong. Finally, we tend to forget information that we don’t use regularly. More importantly, the sponge model is flawed because it treats learning as an event—a moment in time in which knowledge is imparted. In fact, in Maplerivertree’s perspective, learning is a process - this is how we consistently approach management, such as in Decision-making Management, Implementation Management, and Change Management.

The Learning Process

Acquiring Information: If people in an organization are going to learn, the organization must first assemble data to work with. That data could be created inside the company through experiments or brainstorming or it could come from outside the organization via news clippings, experts, consultants, observation, benchmarking visits, or targeted analysis.

Interpreting Information: As the former Dean of Harvard Business School Stanley Teele liked to tell his students, “the art of management is the art of making meaningful generalizations out of inadequate facts.” Even after raw information has been acquired, it won’t be worth that much unless managers can figure out how they analyze and understand it—what we call “interpretation.”

Applying Information: No analysis will matter if it isn’t acted on. The twofold goal in this stage is, first, to translate your interpretation into concrete behaviors and, second, to ensure that a critical mass of the organization adopts these new behaviors. Note how the Army has a systematic process for disseminating lessons and best practices for implementation in the field. What keeps so many businesses from doing the same? Common barriers include the following:

Unclear implications: Not all interpretations of data have obvious implications for action. For example, if a company agrees that a competitor’s big price cut was due to excess inventory rather than an attempt to gain market share, it still has to decide whether and how to respond.

Complacency: When times are good, many companies become complacent and fail to keep up their efforts to improve and innovate. That invites competitors to get ahead.

Bad habits: Even if the implications for action are clear, organizations can have a hard time breaking bad habits, such as overconfidence in a market position or overly bureaucratic processes. That’s how IBM fell in the 1980s.

Risk aversion: Most organizations are built on stability and predictability. Something new might fail. Unless there are strong incentives to learn and experiment, new initiatives are likely to lack support.

Conflicting incentives: When an organization learns something new, it also paradoxically finds it difficult to respond to that learning because the incentives and metrics of the organization are organized around the old way of doing things.

How can organizations best overcome their learning disabilities and cultivate more supportive learning environments? Four conditions allow learning to flourish:

Recognition and acceptance of diverse perspectives: Just as organizations can improve decision-making by encouraging dissent and debate, they can enhance learning by bringing together divergent points of view. Otherwise, it’s the same old same old.

Provision of timely feedback: Timely, accurate feedback from internal and external sources aids in learning and implementation. Ideally, organizations should compress learning cycles to receive feedback and identify problems early. Teams might use prototypes to question their assumptions about customer needs and uncover design and manufacturing conflicts.

Pursuit of new ways of thinking and new information: Learning requires a steady supply of new ideas. Companies may focus externally and “steal ideas shamelessly.” They can also focus internally, by creating discussion forums, targeted experiments, and reflective processes that flush out ideas. They can also put in place incentives that encourage risk-taking.

Acceptance of errors and mistakes: Employees must feel that the benefits of pursuing new approaches exceed the costs. Otherwise, they will fear making mistakes and not take a chance on contributing. Teams should therefore seek to create an atmosphere of psychological safety.

Reviewing incentives and metrics: Incentives need to be constantly reviewed and updated to reflect new learning. Otherwise, you've created tension between what you want the organization to do and what they are rewarded for doing.

Reflecting on Past Experiences

Earlier, we mentioned three channels of organizational learning: reflection, intelligence gathering, and experimentation. These three processes fit together well, as each has a different orientation. Reflecting on experience is aimed at the past, gathering information is focused on the present, experimentation is aimed at the future.

For management, as for pretty much any other skill or practice, certain types of knowledge and behavior come not from thinking, but from doing. Yet, one can only learn so much in real-time, especially when engaged in something new. Conscious reflection is necessary to correctly interpret the experience and thus to really learn from it. In such situations, a manager learns best by carefully reviewing past experiences to distinguish between effective and ineffective practices, developing a hypothesis, and applying the lessons to the present situation. And then, of course, disseminating the findings far and wide to make sure that other employees learn from this experience.

But few managers and organizations build in time for such systematic review. And even if they do, other factors can reduce its usefulness. Some organizations only hold reviews to nail blame. Others groups conduct reviews for the right reasons but have difficulties disentangling subtle cause-and-effect relationships. Reflection isn’t easy to do well. Maplerivertree recommends taking a moment to schedule weekly reflection time in the calendar. Choose a time towards the end of the week during which you can reflect on that week’s performance. It doesn’t have to be lengthy—just 15 minutes per week. One may use a journal or tracker to capture their thoughts. During this time, conduct an AAR (After-Action Review) of your or your business’ performance over the past week. Ask: What did I set out to do this week? What were my goals? What happened? How was my performance? What progress did I make? What progress did my team make? What setbacks did I/we encounter? Why was our performance better or worse than expected? What can I/we do next week to better reach my/our goals? You might review your answer to that last question on Sunday night or Monday morning in preparation for the week ahead. Try this out for a month and see if your performance changes.

For teams and organizations, reflection comes in two main forms: reflecting on failures and reflecting on successes. Both are essential to effective learning.

Learning from Failures: Let’s first examine failures. As Henry Ford noted, “failure is simply the opportunity to begin again, this time more intelligently.” It’s no coincidence that many successful business people — LinkedIn cofounder Reid Hoffman, Amazon king Jeff Bezos, director Steven Spielberg, mega-designer Vera Wang, and even Walt Disney — have cited past failures as major reasons why they were able to succeed next time around. Thomas Edison, who tried more than 10,000 times to make a light bulb, joked that he understood “definitely over 9,000 ways that an electric light bulb will not work.” So there's a lot of talks out there nowadays about learning from failure and about failure being good. We don't see it that simply. Failure is not necessarily good or bad but comes in at least three categories. There are predictable and preventable failures. Those aren't so good. Let's not have them. Then there are complex failures where we face some variability — a set of different variables might come together in a new way that's never quite happened before, and something goes wrong. That's OK, and the key is for the organization to understand them, and thus learn from them. We need to go forward as best as we can. But the third kind is the ‘intelligent failure.’ Nobody could have known this would happen going forward. It was a reasonable experiment. It was a good idea. These intelligent failures are part and parcel of innovation. There’s simply no way to innovate without intelligent failure. So by all means, we should learn from all three kinds of failures, but we should not treat them the same way.

In order to learn effectively from any kind of failure, managers have to frame failure as the very treasure it is, especially intelligent failures. So managers have to say, let's fail often, and let's fail early so that we can succeed later. That's a framing statement. It's letting people know that failures will happen, and so our job is to make them happen smartly, soon, and effectively, and learn from them. Some of the very mundane, day-to-day behaviors that managers can exhibit to reinforce a learning frame and to create psychological safety are being accessible, inviting others' input, and periodically acknowledging fallibility. And there are two kinds of fallibility. One is my own. As a fallible human being, I'm going to make mistakes. I'm going to miss things. I need to hear from you. When I periodically send messages like that, it reinforces a shared understanding that there is uncertainty. There's complexity. And none of us is as smart as all of us. So I'm sending that message in a constant way to let you know I know I'm a fallible human being as we all are, right? You know you're fallible. They know you're fallible. They just don't know that you know. Close that gap. The second thing is when I'm proactively inviting others' input, as if I'm asking questions. People will generally be very willing to tell you what they think. So it creates psychological safety. It creates a sense that it's true that you're interested in people's ideas.

Learning from Success: While organizations inevitably examine significant failures, they often underestimate the value of revisiting successes. The biases that can contribute to failure often cloud the truth about success. As the organizational theorist David Nadler noted, “An unproductive success occurs when something goes well, but nobody knows how or why.” And you may be surprised how hard it is to know exactly why you succeeded. This is why the US Army conducts AARs after every training event and deployment—good or bad. They want to know what should be continued in order to be just as successful next time around. To conclude, here is a list of Dos and Don’ts for reflecting on your own experience and conducting team and organizational reviews.

Gathering Intelligence

For all its power, learning from past experience has a big drawback: it takes place after the fact. Managers and organizations therefore must be skilled at another type of learning: gathering information from their surroundings. Businesses must understand customers and competitors, economic and demographic trends, new technologies and regulations, and their own standing in the marketplace if they are to improve and stay relevant. Managers need to know if their strategies are working, whether their projects are proceeding as planned, how their employees are performing, and how they are doing in their own roles. Three methods of gathering information are especially important:

Gathering (and disseminating) intelligence

Asking for (and providing) feedback

Seeking (and giving) advice

Gain and Disseminate Intelligence: Like organizations, managers must gather knowledge and disseminate it—sometimes to their own people, sometimes to other departments, or to the organization as a whole. Intelligence gathering can be passive or active. The passive gathering seeks information that already exists. Strategic planners, for example, may draw on news articles, databases, and company websites. R&D folks might watch patent filings and attend conferences on the latest technologies. All managers can draw on personal contacts within and outside their companies to stay “in the know.” Active gathering generates new information. Managers use surveys, user interviews, focus groups, and other direct observations of customers, competitors, and employees to gather the information that may exist in people’s heads (or may not exist even there) but have not yet been organized in a meaningful way. Whatever the method, the intelligence-gathering process remains the same: decide what information to seek out, figure out where to look, gather and interpret data, and (ideally) document and disseminate key interpretations that will help others make decisions. Here are some Dos and Don’ts:

Getting Feedback: The gathered information we’ve been discussing so far may be useful, but it’s likely to be impersonal. It’s about the market or the technology or the competition, but it’s not about you and how you’re doing. So managers also need to seek feedback about their own performance. Good feedback is hard to find, but managers can increase their chances of getting it by asking someone they trust to give it, then posing clarifying questions to help better interpret the feedback and creating an action plan to change their own behaviors based on the feedback. Above all, managers should seek feedback regularly and keep an open mind during delivery. That’s hard enough on the nerves, but there’s more. Managers must not only be open to receiving feedback, they must also be able to give it effectively—and for most of us, that’s hard, too. Many managers abhor the idea of giving harsh feedback. They might hurt the person’s feelings or damage their relationship with that employee or with his or her colleagues. As a result, they avoid giving negative feedback or bury it in “feedback sandwiches”—praise, followed by a bit of criticism, quickly followed by more praise—so the subordinate isn’t sure how important the criticism actually was. Effective feedback has to be based on fact—and facts require careful observation. Note also how the change Meghan suggested was specific and actionable. She didn’t say, “Try to be more available.” She said, “Come out of that room and sit in this room.” Here are some more tips on giving and getting feedback:

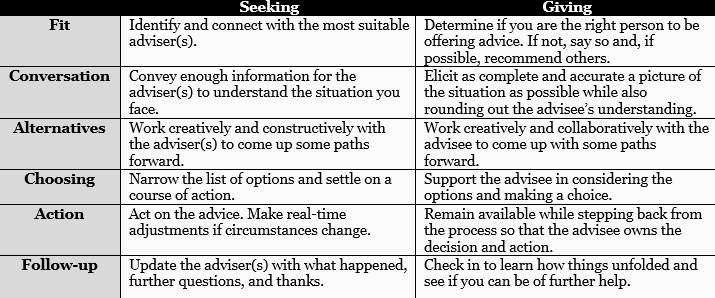

Seeking Advice: A final, often underused, method of gathering information is to seek advice from experts, mentors, and colleagues. As Thomas Fuller, the seventeenth-century English historian and churchman, wrote, “Despise not counsel. A Man is never nearer to Ruin than when he trusts too much his own Wisdom.” Too many managers try to go it alone. The key to getting good advice rather than bad is doing your homework. Here’s a diagram showing how to flunk the test, with misguided choices at every turn:

The biggest mistake is the first one: picking the wrong adviser based on the wrong criteria. For example, seeking advice from a close personal friend who isn’t an expert in the matter at hand or from a colleague who you already know agrees with you. Having found an advisor, managers often proceed to vent, omitting essential but unflattering details and making it hard for the adviser to understand the situation and add value. This is a way to seek affirmation, not advice, and it won’t help. Here’s how to get the process right:

As long-time Professor C. Roland Christensen from Harvard Business School said, “When you pick your adviser, you pick your advice.” Finding the right fit between you, your adviser, and the situation is key. Be upfront about what you are asking for: A sounding board? Perspective? Help to make the decision? Based on the adviser’s role, the two of you need to develop a shared understanding of the problem and come up with multiple possible courses of action. Ultimately, it must be you who decides how to use the advisor’s advice.

Managers also need to know how to give advice when asked. Yet here, too, they run into problems. First, managers are often too quick to dispense solutions without fully understanding the problem. They jump to conclusions without hearing the whole story or overgeneralize from their own experience or accept the advisee’s story at face value without asking clarifying questions. The advisee gets advice, but it’s not of much use. A manager may smother the advisee with too many ideas and options to be useful. Thinking of every angle is fine, as long as you then help the employee narrow it all down.

Managers may attempt to express empathy by providing examples from their own lives that may not actually provide any value. But the biggest problem is that many managers have an inflated sense of expertise and are happy to hand out advice on matters they don’t know enough about. Their best advice would have been to tell the advisee to find someone who really knows that subject.

Here are some final tips for seeking and giving advice:

Experimenting with New Approaches

When situations are novel or relationships between variables are difficult to disentangle, however, neither past experience nor current information is enough to lead you to a good decision. Carefully constructed experiments are then the only way forward. Experimentation is not rare in most corporate settings, and typically comes in two main varieties:

Exploratory research

Hypothesis testing

Exploratory experiments are especially useful to test new, innovative products for which no defined market yet exists. In such situations, traditional market research is of little use because consumers have no clear basis for stating their preferences. In fact, traditional market research will often provide unhelpful or misleading information. The combination of past experience and conventional sources of information leads to severe errors in judgment. Some legendary examples: An 1876 internal memo at Western Union had the following to say about a new product in development: “The telephone has too many shortcomings to be seriously considered as a means of communication. The device is inherently of no value to us.” Almost 70 years later, Thomas J. Watson, the chairman of IBM, remarked: “I think there is a world market for about five computers.” These examples are easy to laugh at in hindsight. But it can be difficult to determine how useful a product can be before it’s launched. Steve Jobs once commented, “Some people say, ‘Give customers what they want.’ But that’s not my approach. Our job is to figure out what they’re going to want before they do. I (Jobs) think Henry Ford once said, ‘If I’d asked customers what they wanted, they would have told me, “A faster horse!”‘ People don’t know what they want until you show it to them. That’s why I never rely on market research. Our task is to read things that are not yet on the page.”

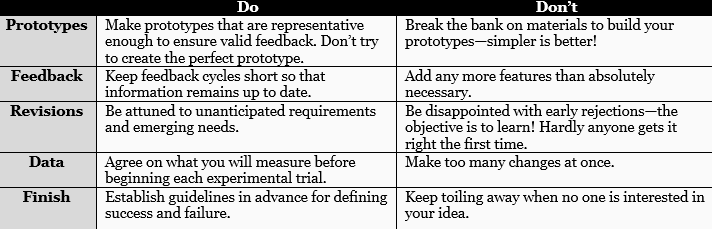

How should managers respond when they remain uncertain about the value of their products? Several scholars have suggested “probe-and-learn” processes. The idea is to develop a product by “probing” (that is, testing, exploring, investigating, examining, finding the limits of, etc.) potential markets with early versions of the product, getting useful feedback and probing again in an iterative process until the company believes it has a winning combination.

Probe-and-learn processes have four critical elements:

A viable starting point: The first product should not be perfect, but merely “good enough.” In startup lingo, the company should aim for a “minimum viable product”—an MVP—that generates sufficient interest among users to get them to try it and provide reactions.

One or more feedback loops: Once the initial trial is underway, the company needs a way to collect information from users and channel it to those who will work to improve the offering.

A process for redesigns/revisions: The team needs a process for incorporating some useful feedback into the next design of the product. After the redesign, it can then be market-tested again and more feedback gained for another iteration.

Some stopping rule: A rule is needed to avoid endless fine-tuning and wasting time on dead ends. At some point, either the product is good to go (despite some imperfections) or managers must pull the plug.

This methodology of experimentation can be applied not only to products and services, but also to new ventures, projects, business models, markets, technologies, operating systems, and even organizational structures. You may notice that the cycle of getting feedback, making small adjustments, and trying again is the same as in our seven-step implementation process for plans and projects. This is not a coincidence. Especially when managers have limited information on what it will take to succeed, the use of experiments will be incredibly valuable. Here are some Dos and Don’ts for exploratory experiments include:

Hypothesis tests are designed for a different goal: to discriminate between alternative explanations of a phenomenon. Say, for example, that customers are not buying as much of a new product as predicted. Is it because the price is too high, the product lacks key features, advertising was ineffective, or a competitor’s offering is superior? Some sort of experiment is needed to rule out at least some of the competing explanations. (Remember, there might really be several factors at work.) You can alter one or more factors, while leaving all others constant, in order to see what’s actually making a difference and how much. For example, you can drop the price of your product, while leaving all the features and advertising the same, to see if demand increases. If it does not, run another hypothesis test in which, say, you add a feature but leave the price and the advertising unchanged.

In its simplest form, the goal of hypothesis testing is to find out why things happen, as opposed to just knowing how things are done. For instance, a steel manufacturer may know how to control temperatures and pressures to align grains of silicon and form silicon steel. But it still might get many defective batches if it does not understand the why—in this case, the chemical and physical processes that produce the alignment.

You won’t be surprised to hear that conducting methodologically sound hypothesis tests is easier said than done. But it’s not magic; it’s a skill and you can learn it. For example, you can learn how (and why) to use proper control groups and random assignment, which is more than most managers know. Hypothesis testing also requires a particular mindset: whatever you think you and your organization already know might actually be wrong, or at least incomplete. And that, of course, can run smack into organizational culture and politics.

The good news is that you do not have to adopt a full-blown scientific approach in order to benefit from hypothesis tests. Methods can be altered to accommodate the realities of the workplace. Experimentation is, after all, as much a mindset as it is a rigid set of rules. Many hypothesis tests provide valuable information as long as they meet two basic conditions:

They firmly establish the relationship between cause and effect.

Results are generalizable beyond the experimental setting.

To meet these conditions, here are a few simple guidelines for designing your experiments:

Have a clear goal: What knowledge do you hope to gain? What relationships do you hope to investigate? What practices do you hope to understand?

Articulate a hypothesis: Develop one or more explanations of the phenomenon you are investigating. A hypothesis is simply an “if-then” statement; for example, “If we allow employees to work from home two days a week, then productivity will go up five percent.” The best hypotheses are specific, unambiguous, and describe a relationship between two variables that is capable of being disproved.

Carefully quantify variables: State upfront what will be measured and how. In studying the impact of a work-from-home policy, for example, you must decide what “work-from-home” and “productivity” actually mean. How many days per week would the policy be for? Does working at Starbucks count? How about working while you’re doing your laundry? How will you measure productivity? Will data be self-reported? Or will it be collected by managers?

Run a carefully designed experiment: Conduct your test under as close to real-world conditions as possible, otherwise, your findings are unlikely to be useful. To isolate presumed cause-and-effect relationships, manipulate only a single variable at a time. For example, don’t install new technology or change other work policies the same week as you begin your work-from-home experiment. If productivity changes, it will be impossible to be sure which change caused that. Finally, use a control or comparison group (a group that does not experience the change) to compare with the treatment group (the group that does experience the change). For example, you would want to introduce the work-from-home policy only to certain employees, departments, or offices so that you can compare what happens with them to what happens with those who did not experience any change.

Analyze the results from different angles: Interpretations of data may be very different depending on one’s position or department, so have a diverse group of observers analyze the results. For example, you might want to have not only HR managers analyze your work-from-home results, but also representatives from other departments.

Use multiple trials: Conduct the experiment multiple times to make sure the findings hold up under different conditions. For example, you may conduct the work-from-home study multiple times throughout the year with different groups to see if seasonality, geography, or other unexpected variables play a role.

Draw a conclusion: Based on the findings from multiple trials, you can reject or fail to reject your original hypothesis. For example, if you see a marked productivity increase associated with several trials of the work-from-home program, you can assume that it has at least some impact on performance. After a few re-tests to confirm that result, you may then want to institute it across the organization.

Leading Learning

We’ve now discussed why learning matters and examined the three stages of any learning process. We also Maplerivetree’s perspectives in terms of the three essential methods of learning—reflecting on past experience, gathering information from the environment, and experimentation. But none of these processes will succeed unless you have created a climate and culture in which learning can flourish. That means diverse perspectives are recognized, feedback cycles are short, new ways of thinking are encouraged, and errors and mistakes are accepted rather than punished. In short, you or your management teams must become a leader of learning. Only then will your people adopt a learning mindset.

Create the Opportunity

For managers, it’s often true that “the urgent drives out the important.” To shift emphasis toward learning and improvement, they must take on a different role, that of a designer who is creating opportunities to learn. They need to construct and run learning forums—assignments, activities, and events whose primary purpose is that employees learn.

The setting doesn’t have to be a classroom. It can be daily standup reviews or recurring guest instructors. Other forms include benchmarking visits, quarterly offsite retreats, or even weekly meetings to watch TED talks to spark new ideas. Whatever the form, the trick is to ensure that learning goals are well defined and that the leader fosters a learning orientation even as the group strives for high performance.

Set the Tone

Setting the proper tone for learning requires creating an atmosphere of healthy skepticism and debate, in which people are free to challenge one another’s assumptions—but not to attack each other, either directly or with sarcasm. The leader might, for example, advance partially developed proposals to spark discussions. The leader could tweak his or her decision-making process to increase constructive conflict and stimulate inquiry. Such techniques to create more open conversations not only make for better decisions but also encourage faster, more effective learning on the way to those decisions. Challenge and dissent won’t result in learning, however, unless the manager has created a sense of psychological safety; for example, by rewarding intelligent failures and providing incentives for experimentation and risk-taking.

A final element of tone is open and equal access to information. Managers must clearly convey that information is an asset to be shared, not a private source of advantage. To overcome the mindset that “knowledge is power,” leaders can alter incentives, rewarding team members for documenting knowledge in a way that everyone can use. They might also redesign the work so that people need to work together in order to get the job done. Many teachers use the “jigsaw” method in their classrooms, in which each student at a table is given only one piece of information. They all have to share what they know or no one can finish the assignment.

Lead the Discussion

With learning opportunities and a learning tone in place, learning discussions can begin in earnest. To lead them, managers need three skills: questioning, listening, and responding.

Socrates based his method on asking questions because they encourage people to think. Unfortunately, most managers prefer bold assertions over subtle questions, which they sometimes view as a badge of ignorance. But as Peter Drucker argued, “the most common source of mistakes in management decisions is the emphasis on finding the right answer rather than the right question.” Questions can be used to frame issues, solicit information, probe for analysis, make connections, and seek opinions.

Having posed a question, the manager must also listen attentively to the ensuing conversation. Listening requires patience and a willingness not to interrupt or jump to conclusions until all the information is on the table. As the transcendental writer Henry David Thoreau put it, “It takes two to speak the truth—one to speak and another to hear.” Managers must not only listen to what is being said, but how it’s stated; effect and tone are as important as content.

Finally, managers must practice how they respond to information being created. It doesn’t help to shoot down an idea as soon as you find a flaw in it. But neither does it help to remain silent and seemingly disinterested. Instead, you need to encourage the speaker, ask for clarification, provide suggestions, express respectful disagreement, and criticize when employees break the norms of conversation. In short, if the goal is learning, the manager must be a teacher.

Fostering Individual Learning

As you may have noticed, whenever there are three requirements, there’s bound to be a fourth. So here it is: To lead learning, a manager must be committed to learning himself or herself. That means remaining open to new perspectives, increasing your self-awareness (especially when it comes to personal biases and tendencies), and seeking out raw, unprocessed, unfiltered information. To do these things, of course, you need to let others speak their minds. Above all, Maplerivertree recommends that you must foster a sense of humility, you must recognize that you don’t have all the answers - Many, we hope, but not all, and you need to recognize what you still don’t know and show that you’re willing and able to learn it. ■