Decision-making Management

Decision-making: a Core Process

The continuous refinement of four key processes is critical to strong business management. They are 1) Decision making, the process of identifying problems or opportunities and choosing from among various courses of action, which is the focus of this page; 2) Implementation, the process of executing strategies, plans, and other choices effectively and efficiently, about which you can read more here; 3) Organizational learning, the process of acquiring, interpreting, and applying new information and ideas to be able to perform effectively, make improvements, or innovate, about which you can read more here; 4) Change management, the process of guiding or leading an organization through internal or external transitions or shifts, about which you can read more here. Maplerivertree helps client businesses examine and develop decision-making processes to solve known challenges and build stronger management.

Decision-making is a hot topic today. Whether it's some new book documenting the host of cognitive biases we have, or a new article providing a framework for making better decisions, there's no shortage of advice out there on the subject. All this material is often intriguing. Much of it is, surprisingly, unhelpful for organizations. Why? Three reasons.

First, it approaches decision-making from the standpoint of the individual rather than the team. But in modern organizations, decision-making is rarely a solo endeavor. Second, it focuses almost exclusively on biases and pathologies. But by very nature, these are difficult to overcome and mere awareness of them is not enough. And third, much of it offers few tactical recommendations or practical guidelines. As a result, management teams are left in a bind. All too often the answer to the question, how can I best improve our organization's decision-making, is it depends. Every situation is viewed as unique. A reflection of the distinctive features of the environment, the issue, and the participants. Few managers are equipped with a broad, unifying perspective, a set of simple techniques, and approaches to decision-making that will improve the odds of their team's success. And because of this, teams and organizations have a tough time learning from past decisions to make better ones next time around.

At Maplerivertree, we'll consider decision-making from a uniquely powerful point of view, the process perspective - this is how we approach management and you can read more about it here. In particular, we examine what managers can do to shape our clients’ group decision-making processes within their organizations. To that end, we explore some of the mythologies around organizational decision making, the key elements of a good decision, and the process choices that managers need to consider when looking to shape the decision-making process.

Myths and Realities of Organizational Decision-making

As with management itself, there are a lot of myths about decision-making out there. Let’s look at a few of them and figure out why they are so pervasive.

The Myth of the Lone Warrior: then we read in the news about a company’s failed strategy, we tend to wonder, “What was the CEO thinking?” But is that the right question? Is it really the CEO who “makes the call?” As a manager, how often do you “make the call” in a given year? In reality, managers hardly ever do so. In fact, studies have shown that, in a given year, managers make only a handful of decisions on their own. As former General Electric CEO Jeff Immelt said: “There are only about 3–18 times a year when I can say ‘do it my way.’ Do it 18 times or more and the good people will leave. Do it less than 3 times and the organization will fall into chaos.” This myth of the “lone warrior” who blew it is one of several myths that keep us from learning from others’ mistakes and making better decisions ourselves.

Decision-making occurs at a defined moment: Decision-making is seldom an event—the output of a single pronouncement, meeting, or discussion. It’s usually a process—a sequence of stages that unfolds over days, weeks, months, or even years. In a study of over 150 major strategic decisions, a group of British academics discovered that the time from identifying the issue to making the choice ranged from one month to over four years. On average, the process took over a year! And as we’ll see, when decision-making isn’t a process, it probably should have been. Decision-making is, at heart, a process, one that unfolds over time, that's fraught with politics and debate, and that requires widespread support from teams and organizations when it comes time for implementation. Unfortunately, based on Maplerivertree’s engagement experience, too many managers don't recognize these defining characteristics. They continue to view decision-making as a singular activity or an event.

What are the implications for managers of believing this myth? First, managers that see decisions as events remain overly focused on the meeting, which they see as the occasion for deciding. And they don't attend to other influences. They vastly overestimate their ability to control the outcome because they believe that most of the heavy lifting is done in the room. As a result, they're often blindsided by unexpected voices or perspectives. Second, leaders miss the chance to shape the process as it unfolds. In particular, when leaders view decision-making as an event, they seldom pay enough attention to the early stages of the process, which are often the most crucial. They don't, for example, remain open to multiple options, encourage diverse ways of thinking, or show sensitivity in the face of dissenting or minority views. But decision making doesn't have to be so limited or frustrating. Studies in a wide range of fields, including psychology, economics, management, and political science have shown that the decision-making process can be redesigned and improved. For this to happen, managers need new ways of thinking about the subject, which Maplerivertree will help your organization to develop.

We'll start with the basics. What makes for a good decision? And we'll then dive deep into a set of criteria, conflict, consideration, and closure, which we call the three Cs of decision making that shape the associated decision-making process.

Decisions are made “in the room” with all affected parties present: This is definitely the exception rather than the rule. As a disenchanted executive once told former Tuck professor James Brian Quinn: “When I was younger, I always conceived of a room where [strategic] concepts were worked out for the whole company. Later, I didn’t find any such room.” What he found was that decisions emerged from a multitude of interactions—including one-on-one meetings, small subgroups, and informal conversations—across different levels and departments. And even if a decision does get made “in the room,” the organization may have to revise it if the people actually implementing it weren’t in that room at the time.

Most managerial decisions are based on careful analysis of a problem and a thoughtful comparison of the costs and benefits of various options: Even the most analytical bean counters know that this isn’t so. It’s not that rational analysis of the options can’t play a part, but it’s rarely the leading part. It’s typically trumped by social, emotional, and political factors. The process is usually characterized by coalition-building, intense bargaining, negotiations, and persuasion. Emotions and gut feelings often override logic.

Describe a situation in which you or a colleague let the quest for a “perfect” decision interfere with finding one that was “good enough.” How long did that decision-making process take? What was it like implementing it? This is a shared reflection, so you may wish to be vague about the details. In effect, decision-making is more a process for deciding which tradeoffs various parties can live with than a search for the “right” answer. The “best” solution—the one that is analytically or conceptually superior—is often less useful than a timely, easy-to-implement, “good enough” decision amenable to multiple parties.

Management first analyzes the problem, then decides on a course of action, and finally implements it. The classic model of decision-making found in most business textbooks goes something like this: first, identify the problem or opportunity; second, gather information and analyze the problem; third, define criteria for evaluating solutions; fourth, generate alternative solutions; fifth, weigh the costs and benefits of each option; sixth, select the option with the highest expected value; and seventh, implement the decision.

This can even happen! But it hardly ever does. For one, decision-making is seldom a linear process. It’s common for groups to skip steps, go out of order, and/or return to earlier steps they thought they had completed. For example, managers often make a decision based on certain assumptions and with a solution already in mind. When they find out they were wrong from the start, they may have to go back to Step 1 and start over. (Of course, they don’t have to reconsider. They can keep doing what they’ve set their minds on despite the evidence. A failure is always an option.) In addition, groups often find it difficult or impossible to keep the stages of decision-making separate. It’s very tough to analyze problems without thinking about solutions or to develop solutions without judging them.

Evaluate the Process, Not the Outcome

What is it that separates good decisions, like Apple bringing back Steve Jobs, from terrible ones, like Enron repeatedly cooking its books? The first question you need to ask is how much weight I should give to outcomes and how much to the processes employed. Focusing on outcomes has an important drawback. Hindsight is 20:20. It's all too easy to look at someone else's blunder. And say, that with my organization, my department, my team, or my intellect and experience, things never would have turned out so badly. We would have made the right choice. But this is dangerous thinking for two reasons. First, when evaluating past cases of decision-making, we always have the benefit of knowing how things turned out. In retrospect, it's easy to pinpoint suboptimal decisions. Had we been in the shoes of the decision-makers at the time, however, the very same situational pressures, weak signals, institutional inertia, and biases might well have led us to make the same choices. Second, when we evaluate decision-making by its outcomes, we're actually measuring, precisely, the wrong thing.

Your management team’s focus should be on the associated processes used to make decisions, and, in particular, how well they were designed and managed. Why? Because successful outcomes can also be the product of simple luck, chance interactions, or even unexpectedly favorable changes in the environment. In such cases, success is seldom repeatable. To get good results, first, develop a superior decision-making process. That is the key lesson of this module and one that should become second nature as this program unfolds.

At this point, you are undoubtedly thinking, “Okay, enough with the build-up. What are the elements of a good decision-making process? And will it guarantee good decisions?” The answer to the second question is easy: No. Nothing guarantees that you’ll always make the right decision. Nothing even guarantees that there is a right decision. But by focusing on your process—over which you have considerable control—rather than the outcomes, you will probably win in the long run.

Here’s Kevin Sharer, former chairman and CEO of Amgen, to describe some effective elements of his decision-making process:

“So the first thing is to get the best team and listen to them. So part of our decision process was to get the right people in the room and really talk openly about the issues. The second thing was to fully discuss what we thought the feasible options were, and what the risk and benefit of those options were. We used to have a phrase, which went to risk I suppose. Is the view worth the climb? Is it going to benefit us enough that the risks were worth it? So we'd try hard to think about risk.

Next thing we tried to do was get a consensus. Not consensus in the literal sense, where everybody agreed and everybody had a veto, but try to find a solution that everybody could support. Now theoretically you can tell people, hey, you were heard, you don't agree with the decision, we went a different way, too bad, do it. Well, in real life that's hard to pull off. And then finally, I used to say as CEO I've got 51% of the vote if I need to. I think in 12 years as CEO, I might have done that two or three times. I'd be very, very reluctant to use my 51% of the vote because what that means is I'm sort of ignoring the advice of my colleagues.”

A good decision-making process has the following three key elements.

• Quality. It involves careful, rigorous analysis of the problem and thoughtful comparison of the options.

• Executability. It creates collective buy-in and increases the odds that the decision will be executed well.

• Timeliness. It is neither too early nor too late.

Case study: John F. Kennedy’s decision-making in the Bay of Pigs

Let's go back in time to the Cold War. Time of intense political tension between two major powers, USSR representing communism and socialism, and the United States, representing democracy and capitalism. These two forces were at loggerheads. They were very much two different views of the world. Then in 1959, a third actor gets added to the mix, Cuba. In 1959, Fidel Castro leads a revolution. He and his party overthrow the dictator, Batista, and nationalize US businesses. In response, the United States severs relationships and Cuba becomes aligned with the Soviet Union. The upshot? The US now has communism in its backyard. It's with this backdrop that on 20 January 1961, John F Kennedy steps into office as the 35th President of the United States.

“I, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, do solemnly swear. I will faithfully execute the office of President of the United States.” Two days later, the Central Intelligence Agency, led by Allen Dulles, briefed select members of JFK's administration on a to top-secret plan to employ Cuban exiles in an invasion of their homeland. The CIA also hopes to install a provisional government on Cuban soil to support a free Cuba and rid the country of communists. Six days later, Kennedy convenes his first White House meeting on the plan. Members of multiple departments and agencies attend to review the CIA proposal and make the case for a possible course of action. The first, and one of the most impactful decision-making processes of Kennedy's presidency, is about to unfold.

Rather than engaging in—or, we might say, submitting to—a rational analysis of the Cuban problem and a cool determination of the best course of action, the personalities and agencies involved in this decision-making process all brought their own personal, political, and historical biases to the table. Want to see how well that worked?

Fast forward to April 1961. The president has just made his decision. He has given the go to the rebels' invasion of Cuba. And the outcome? It's a disaster. Around midnight of April 17, the rebels land in the Zapata area near Cochinos Bay, the Bay of Pigs. Within hours, they're detected by Castro and his forces. Various airstrikes and decoys by the US-backed rebels over the past few days have not done much to attract attention away. By 6:30 AM, Castro's military has begun its attack on the invaders. It takes Castro's forces only three days to defeat the brigade of exiles. By the end, 118 of them are killed, and 1,202 are captured. The invasion is not only a policy failure, but also a political embarrassment for the Kennedy administration. On April 21, Kennedy sits in a State Department press conference, about to respond to questions and comment on the debacle. He's still puzzled by the outcome. He and his team had developed their positions carefully. They'd come to a consensus on the best course of action. They were all committed to their selection, and relatively confident the plan would work - or so he thought. What could have led to such a poor outcome for Kennedy and the US?

President Kennedy’s failed invasion of Cuba is considered by many historians to be one of the worst foreign policy decisions in US history. How did such a smart, respected man, supported by a team of experienced advisors, make such a poor choice?

In short, JFK managed the decision-making process poorly. In particular, he failed to pay attention to two key factors:

the mindset of the participants

their method of analyzing problems, generating solutions, and coming to an agreement

Mindset: Advocacy vs Inquiry

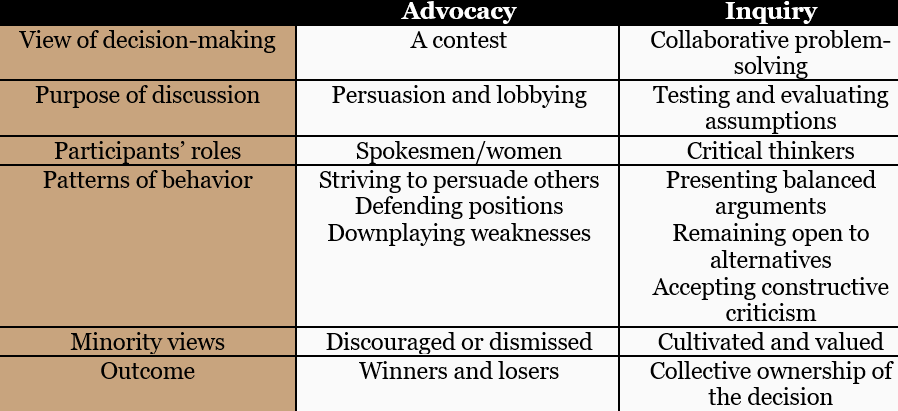

When making a decision or tackling a problem, participants can adopt one of two philosophies, perspectives, or mindsets.

One approach is advocacy or persuasion. Group members come into a meeting with pre-defined notions of what the problem is and what should be done. They take parochial, departmental, or divisional views, and they implicitly define success as having their own view prevail. They approached the decision-making process as a contest, arguing passionately for their preferred solution, and standing firm in the face of disagreement.

Contrast advocacy with a second mindset or approach, which we'll call inquiry, or problem-solving: A group that operates in inquiry mode tries to start deliberations with as few biases or preconceptions as possible. Members begin with open minds, share all data, consider a variety of options, and work together to discover the best possible solution. While individuals naturally continue to have narrower departmental interests to some degree, the overriding goal is not to persuade others to accept one's point of view, but instead to come to an agreement on the most desirable course of action for the organization as a whole.

On the surface, advocacy and inquiry approaches look deceptively similar. Both involve individuals engaged in debates, drawing on data, developing alternatives, and deciding on future directions. But despite these similarities, inquiry, and advocacy produce very different results.

Advocacy is typically the default mode. One is expected to argue for one’s department or group. But this is a dangerous path to take. It’s difficult to be objective and to pay attention to opposing arguments. Advocates often emphasize whatever supports their position and withhold or downplay whatever weakens it. Personalities and egos come into play, people begin to take disagreements personally, and differences of opinion are resolved through political power or willpower

Inquiry is a much more helpful mindset. People share information widely to aid others in drawing their own conclusions. Rather than suppressing dissent, inquiry encourages critical thinking and the generation of multiple options or points of view. Groups operating in an inquiry mode do rigorously question each other’s arguments and assumptions—so the conflict may be intense. But it is less likely to be personal, since the goal is to find the very best solution, not to win a contest. Team members resolve their differences by applying rules of reason.

In the Bay of Pigs, JFK convinced himself that the decision-making process was inquiry-based, when, in reality, team members were advocating for their own solutions. The CIA, for example, had planned the invasion under the previous administration and advocated strongly for it. The results were predictable. That’s not to say the invasion had to fail. What I mean is that such a poorly managed decision-making process was bound to produce a poor decision—no matter what the issue at hand was.

Method: Structure and process

Method involves choices of structure and mechanics. For instance, does the group discuss options together as a single collective body? Or do they split into subgroups? Method also involves how the roles and the responsibilities of the leader should be defined. Does the leader serve as a final authority or in more of a participatory role? Who, for example, makes the final call? These are essential choices, in part because method often has a significant effect on the prevailing mindset - it sets the tone. In particular, the choice of method can have a big effect on how members go about approaching the task and viewing their own role. The dominance of advocacy or inquiry is determined, to a surprising degree, by how the decision-making process has been designed.

Of the various methods of decision-making, the most common is consensus. But for Kennedy, this method was not well suited to the matter at hand and, in fact, was largely responsible for what went wrong. He might have done better by using another method—for example, one involving subgroups, as he did in the Cuban Missile Crisis, which we will learn about later.

Now let’s ask how JFK could have skillfully shaped both mindset and method to cultivate something that was largely missing from his group decision-making process: constructive conflict.

Analyzing the Bay of Pigs: At the time of Kennedy’s initial briefing on the invasion plan, his cabinet had just been formed; it was only a few days into the start of his administration. The Joint Chiefs presented their analysis very soon afterward. This context—a newly formed team, a combination of experienced and inexperienced players, and an inherited agenda—strongly influenced the participants’ mindset and the way the decision-making process unfolded. Think of instances where you’ve been part of a newly formed team, ideally one whose members were unfamiliar with each other. Contrast the members’ behavior and goals with those of the members of a team with greater familiarity and experience working together. What unique challenges might arise? You probably recalled some social pressures that, in retrospect, you realize affected your behaviors. New members often want to make a good impression and thus do not “rock the boat” by staking out extreme positions or asking tough questions. You may have noticed a similar desire to fit in during the simulation using the consensus method of decision-making.

As JFK learned the hard way, this can lower the quality of the team’s—or the leader’s—decision by stifling constructive conflict. By March, the president is facing a now-or-never decision. The rainy season in Cuba is about to begin, making an invasion even more difficult. The exiles in Guatemala are clamoring to move. And Cuba, Kennedy's advisers have just learned, is about to receive shipments of military jets from the Soviet Union. The pressure is rising. March 11th, a critical meeting. The case for the invasion is made by Allen Dulles and Richard Bissell, senior CIA officials, who had originally developed the proposal under President Eisenhower, JFK's predecessor. Their presentation focuses heavily on the disposal problem-- the challenge of figuring out what to do with 1,000 armed exiles. Probably the best place for them to go, Dulles and Bissell suggest, is where they really want to be - Cuba. But the president is still cautious. He thinks there's too much noise with the current plan. Kennedy is especially concerned with the visibility and prominence of the proposed landing site - Trinidad. Kennedy instructs the CIA and Joint Chiefs to look for a different location. Eventually, they settle on Cochinos Bay - the Bay of Pigs - approximately 100 miles from the original landing site. The cabinet begins to meet every three or four days. Bissell and Dulles continue to make the case for the invasion. There are silent demurrals around the table, but no one speaks up in opposition, certainly, not vocally. Arthur Schlesinger, a Special Assistant to the President, who attended many of the key meetings describes this time as one in which we were operating in a curious atmosphere of assumed consensus. While the team did not vote on the matter, the presumption was that silence, not speaking up in opposition, meant assent or agreement. Meanwhile, Schlesinger was becoming more and more concerned, as were other officials occasionally invited to these meetings. Eventually, Schlesinger arranges a meeting with Dean Rusk, the Secretary of State, to voice his objections. Rusk's says in response, "Maybe we've been oversold on the fact that we can't say no to this invasion." Rusk promises to draw up a list of pluses and minuses and speak with the president, but it's not clear he ever gets around to doing so.

Bay of Pigs: Mindset and Method: Why was there so little constructive (cognitive) conflict when JFK and his Cabinet discussed the invasion plan? There were failings on two fronts: mindset and method. First, let’s look at the group’s mindset. Advocacy dominated inquiry. Instead of developing a balanced assessment of the costs and benefits of an attack by the rebels and comparing that to other options, the CIA pushed its own agenda. Dulles and Bissell came with a clear objective: to get JFK to adopt the plan that they had worked so long to develop. New cabinet members and those lower down in the pecking order did not want to criticize or question JFK or other higher-ups for fear of stepping on toes or damaging their own credibility. How would you characterize the incentives of Dulles and Bissell? Contrast that to Schlesinger and Rusk. What do you conclude?

1. The new boss just came into the office, and my apartment happened to be in the spotlight, we need to act decisively and not admit flaws in our mental model. This is a great opportunity to increase the scope of the agency and visibility to the President.

2. Sunk cost - efforts and capital and time already invested in developing these plans.

There was plenty of conflict during JFK’s decision-making process, but it was personal conflict, not constructive. The CIA and Joint Chiefs took “tough guy” positions. As a result, others kept quiet and left key assumptions untested.

As Amy Edmondson, Novartis Professor of Leadership at Harvard Business School, explains, “avoiding affective conflict is easier said than done. But it needs to be done. Most managers today recognize that conflict is not a bad thing. We first listen to diverse points of view. We welcome dissent, and we analyze, and we come to good decisions. However, this is hard to do. Sometimes managers think, well, let's just have tasks conflict, a conflict that's related to the substance of the work or the decision, but let's make sure not to have any relationship conflict because that's bad. That's about personality. That gets in our way. I love that idea, and it's impractical in practice. In fact, as soon as we start to disagree about the substance, about the task very quickly relationship conflict shows up uninvited because I can't help it. Effectively, I can't help being a little bit frustrated with you when you disagree on something I care deeply about related to the task. Managers need to learn to work through relationship conflicts, not to assume they can be left outside the conference room but to assume that they have a legitimate place in the conference room. That I can talk honestly about my frustrations when you raise that concern. I understand, you see it as a legitimate concern. And I just have to be willing to say, I'm finding it difficult to listen to that perspective, so help me understand it better. Let's walk down again through your thoughts, and then I'd love to walk carefully through mine. So we need to have a kind of honest and forthright willingness to engage both the task and the relationship issues so that we can come to better decisions.”

Recall Schlesinger’s observation that JFK’s advisors “seemed to be operating in a curious atmosphere of assumed consensus.” “Consensus” always sounds like a good thing. But if we think of it as a method—as one possible variety of the decision-making process—we may conclude that it was the wrong method for the circumstances at hand. With consensus, there are strong, implicit pressures to agree. Hard questions, divisive issues, and minority views tend not to be welcome. After all, they are obstacles to what we usually think of as consensus. These pressures were reinforced by the setting. JFK had just arrived in office, and his national security advisers were not yet comfortable challenging each other and speaking freely. Dissent meant arguing with the President only a few weeks into his new administration—not the obvious way to earn his trust.

This combination of advocacy (Mindset) and consensus (Method) was deadly. In the Bay of Pigs, this combination, an advocacy mindset together with a consensus method of decision-making created strong pressures to overlook flawed assumptions, downplay disagreements, and strive to maintain harmony. The resulting smoothing behaviors are often found in groups that people wish to be associated with because they're regarded as prestigious or desirable. This phenomenon is commonly known as groupthink.

According to Irving Janis, a leading scholar on the topic, groupthink is a mode of thinking that people engage in when members striving for unanimity overrides their motivation to realistically appraise alternative courses of action. It involves a deterioration of mental efficiency, reality testing, and moral judgment that results from in-group pressures. In a nutshell, people go along to get along. Groupthink helps explain why Schlesinger did not raise objections to the CIA's plan during meetings and why Rusk never got around to convey his concerns about the plan to the president.

Groupthink

Because groupthink is a product of such ordinary human motives, it can affect any business team. But it is of special concern in two settings: one, a new team whose members are jockeying for power and position, or two an experienced team that has grown accustomed to suppressing disagreements in order to “maintain a united front.”

Here are some symptoms of groupthink, as described by Irving Janis:

Illusions of invulnerability

Collective rationalization and discounting of warnings

Unquestioned belief in the group’s inherent morality

Stereotyped views of the enemy

Direct pressure on any group member who argues against the group’s stereotypes, illusions, or proposals

Self-censorship of disagreement with the group’s apparent consensus

Shared illusions of unanimity

Self-appointed mindguards who protect the group from adverse information that might shatter their complacency

And here are some common unhappy results:

Discussions are limited to only a few options for action.

The option preferred by the majority is not examined critically for nonobvious risks.

Options initially rejected are not reexamined for ways to make them acceptable.

There is little attempt to obtain information from unbiased experts.

Members process information selectively, favoring facts and opinions that support their initial preference.

There is little discussion of likely resistance, setbacks, or difficulties with the preferred option and no careful contingency plans.

Given what you know now about methods of decision-making, cultivating constructive conflict, and reducing affective conflict, how might a team escape groupthink?

— Understand that performance overview is decoupled from relationship bonding

— Management when involved in conflict resolution, abides by truth-seeking, not harmony seeking

Closing the case study: In April, JFK decided to launch the Bay of Pigs invasion. Why did he decide to go ahead? For one, he felt that he had pared down the scale of the invasion. He also felt that it would solve the problem of what to do with the rebels otherwise. Finally, he believed that there were few other options and that his own luck would continue to hold. Arthur Schlesinger later said, “Had one senior advisor opposed the adventure, I believe that Kennedy would have canceled it. Not one spoke against it.” Similarly, had team members come up with viable alternatives to compete with the CIA’s plan, JFK may have felt better able to make another decision. As with the Everest fiasco, this was a classic case of overconfident leaders whose instructions, mindsets, and behaviors ended up stifling opposing views. Groupthink ruled the day.

Devil's Advocacy and Dialectical Inquiry

The process of devil's advocacy can be used in many situations where there's a need or desire to generate conflict, debate, or differing points of view. It does so by assigning an individual or subgroup to serve as the devil's advocate. That individual has a well-defined set of responsibilities. She's expected to probe to uncover underlying assumptions, push supporters to explain their logic and reasoning, clarify points that are ambiguous or obscure, provide additional information that highlights unstated weaknesses, and challenge the initial proposal on both theoretical and practical grounds. The process of devil's advocacy can be used in many situations where there's a need or a desire to generate conflict, debate, or differing points of view. You're likely to be familiar with the concept of a devil's advocate since it's often little more than a synonym for a persistent critic or a contrarian, someone who takes the opposing side in a debate or argument just to stimulate critical thinking. But you may not know the history or derivation of the term.

It actually comes from the Roman Catholic church, and the process used as early as the mid-1500s to evaluate candidates for sainthood. Sainthood requires proof that the candidate has indeed produced a miracle. To make that decision, and ensure that it was rooted in robust debate, the church assigned a small working group with two roles, supporters and detractors. The detractor was called the devil's advocate. He served as an in-house critic, arguing that the individual being considered for sainthood should not be canonized because there were holes in the evidence, unresolved issues about the candidate's character, or conflicting evidence that suggested that the event in question was not really a miracle, but had actually occurred through earthly means.

Dialectical inquiry is very similar to devil's advocacy, with some adjustments to create even more debates, differences of opinion, and divergent thinking. Again, the decision-making group first breaks into two subgroups. One of the subgroups develops a set of assumptions and recommendations, which it then presents to the other subgroup. The second subgroup then develops a different or opposing set of assumptions and recommendations, which it shares with the first subgroup.

The two groups then discuss and debate these alternatives, with the goal of agreeing on a single set of assumptions and recommendations. Note that the final set of assumptions and recommendations can incorporate elements from both proposals, from one of the two approaches, or from neither of the two. While devil's advocacy can be traced to the Roman Catholic church, the dialectical inquiry is usually associated with the German philosopher Hegel in what is now called the Hegelian dialectic.

Although there are echoes of the approach in the writings of Plato and other renowned thinkers of ancient Greece, Hegel maintained that every good argument, decision, or proposal has three elements. A point of view, or a thesis. An opposing point of view, or an antithesis. And an integration or combination of these two points of view, or a synthesis. The process of dialectical inquiry simply institutionalizes this three-step process.

Provisional takeaways: First, every decision-making process has strengths and weaknesses. Of the three we looked at, the consensus method typically leads to high levels of commitment, satisfaction, and group harmony. Groups also find it easier to implement decisions that result from this approach. But they may also lead to premature closure and not enough divergent thinking. In the contrast, the dialectical inquiry and devil's advocacy methods typically lead to more critical evaluation during the process. As a result, they're likely to produce high-quality decisions, but at the same time, may result in resistance during implementation. The lesson should be clear. There is no one best way to make decisions. Given the pros and cons of each method, a manager shouldn't stick with a single universal approach, but should instead respond to the circumstances. For example, the consensus method is usually more appropriate for routine, low-risk, well-structured choices, because those decisions typically take less time and effort, have a known set of alternatives, and often require quick implementation. On the other hand, managers might favor dialectical inquiry or devil's advocacy for ill-structured, non-routine decisions that require creative thinking, and are likely to have a big impact on firm performance. Second, recognize that conflict plays a very different role in each method. Both cognitive and affective conflict is impacted by your choice of method. And without thoughtful intervention and shaping, the two types of conflict tend to move in the same direction. That's an unfortunate reality. While cognitive conflict enhances decision quality and understanding of decisions, it also tends to go along with affective conflict, which decreases decision acceptance, and reduces group harmony. The result — the decreased likelihood of effective implementation or productive group decision-making in the future.

Conflict is thus a mixed blessing for leaders. Their real goal should not be just to stimulate conflict, but to create gaps, to increase decision quality by increasing cognitive conflict, while increasing buy-in, commitment, and satisfaction by reducing affective conflict. And they have key levers to do so.

Shaping the Decision-making Process: the Three C’s

In addition to balancing the three elements of a good decision — high quality, a high likelihood of effective implementation, and timeliness, how does an organization shape its decision-making process to achieve goals? Maplerivertree’s answer is the three C’s. By cultivating diverse perspectives (constructive conflict), giving real weight to all the viewpoints on the team (consideration), and balancing tolerance for open participation with a willingness to close off the conversation (closure), management will make good decisions the norm rather than the exception.

Conflict: We know that disagreement and debate are important to effective decision-making. In the Bay of Pigs, you saw the perils of too little conflict. And in the dialectical inquiry devil's advocacy simulations, you at times saw the perils of too much. Moreover, conflicts have to be of the right variety. You want to create large amounts of cognitive conflict while minimizing affective conflict. But let's take a step back. Why exactly does conflict benefit groups? Why make decisions via a group at all? Why don’t the leader just make the call? The benefit of making decisions in groups is that other individuals can bring different viewpoints to the table and can challenge preconceptions and presumed truths. Why is this so important? Because as William James, the pragmatist philosopher wrote, “a great many people think that they're thinking, when they are merely rearranging their prejudices.” Most of us find it difficult to identify our own biases and to question our own unstated assumptions. Teams provide an antidote as long as they engage in real debates. It's therefore crucial for managers to cultivate constructive conflict in order to stimulate creativity and ensure that people really are thinking. Multiple options, alternative interpretations, diverse perspectives, and wild and crazy ideas all are gateways to higher quality choices.

How does a manager stimulate conflict and debate, especially when people lower than them on the totem pole might be afraid to speak up? Here’s Nitin Nohria, former Dean of Harvard Business School, with some tips:

“The idea of how you get people to bring dissenting opinions to you, to share their views with you openly, is one that a lot of people think very hard about. My answer to this is very simple actually. I have learned that people have antennas. They just know that do you actually care to hear what they have to say or not. And through your body language, through whether you actually listen to them or not, whether you genuinely want to foster debate or not, people will very quickly read the signals of do you really care to have a vigorous debate. Do you care to have a vigorous debate because you're actually going to incorporate what the debate says into the final decision, or do you just want to have a debate? And then the debate ends and then you let people know what it is that you were thinking from the very first minute and it's as if the debate didn't matter because nothing that was said in the debate is something that you then chose to do. So, my feeling about this is that be very careful about the signals that you give off and the experience that people have in any decision-making process with you. Because people will very, very quickly find out whether you actually care to have the debate or not. Frame the topic. If you have a point of view, say to people, here's my point of view so that they're not trying to guess what yours is. If you don't have one, say I don't actually have a strong point of view here, I want to actually get all of your input. Even if you have one, make sure that people know that I have a prior, but I want to have this conversation because I'm not sure I'm right, or if I hear something that I really think we need to think differently about, I'll be sure to do it. People will then speak up. If you frame the topic properly, or if you're transparent about where you're coming from, or if you allow people to when they speak to not get cut off too quickly. Make sure that if someone has the contrarian point of view, and it's a meeting and everybody else is against them, I think one of your jobs as a leader is to side with them, even if you don't agree, to make sure that that viewpoint gets heard. So I've learned that it's very important that there's a minority opinion in the room, to not cut it off too quickly. You as a leader have to say no, let's hold off a minute. Let's hear what John has to say, and let's give them some time, or let's hear what Mary has to say. So, you must allow the contrarian view to emerge. And you must provide support for the contrarian view. And then you must make sure that you listen, that you don't just try and dismiss the contrarian view. If you do that 2 times, 3 times, people know that that's for real, and all of a sudden, the process changes.”

Consideration: Consideration is related to an often-ignored aspect of decision making, the degree to which participants believe that the process is fair. Once a decision has been made, some participants in the discussion will have to give up on the solution they preferred. In some cases, the people who were overruled resist the outcome. But in other cases, they display grudging acceptance. What causes the difference in these two responses? Research indicates that a key factor is the perception of fairness, a process that was open, legitimate, and did not have a rigged or predetermined outcome. The reality is that while top managers often make the final call, people participating in the process must believe that their views were considered and had a genuine opportunity to influence the final decision. Otherwise, they'll lack the commitment to the decision, which is an important determinant of their willingness to implement.

Some elements of fairness are obvious. For example, in a fair process, you have a voice—a chance to speak up and express your views. In an unfair one, you don’t—or somebody else doesn’t. Beyond that, in a fair process, you feel you actually have a shot at influencing the outcome. In an unfair one, the outcome seems pre-ordained. The process is a sham. Fair processes are also transparent; that is, whether or not you agree with the final decision, you understand why and how it was made. (For example, even if you aren’t happy about who won a Presidential election, you know that the votes were counted and then the Electoral College votes were added up and that’s why the winner won.) Decisions seem unfair if you don’t really understand how in the end they were made. (Imagine, for example, an election in which you vote, and the next day a winner is announced, but nothing is revealed about who got how many votes.)

One obvious problem is that the subgroups had a lot of influence but nobody outside them knew for sure what that influence was. Also, there was little consideration and little opportunity for influence in the ratification stage. This is probably why people sometimes felt that it wasn’t over, even after a decision was officially made.

How do you get it? Most managers equate fairness with a voice, with people's ability to speak up. But there's more to it than that. Equally important is demonstrating consideration. That is showing people that you actively listen to them and weigh their views carefully before deciding. Leaders should avoid a common trap, stating strongly-held positions at the very start of discussions. Instead, they need to remain open to alternatives and different ways of thinking. Active listening during the discussion is important for conveying such openness. Managers can, for example, ask thoughtful questions, actively take notes, play back points of view to ensure that they were heard properly, and make sure others do not interrupt one another during debates. Transparency matters too. It includes providing a process roadmap on how the team will come to reach a decision with the roles and responsibilities of participants clearly stated. Most important of all is a logical explanation of the decision. A leader must be able to state his or her rationale for the decision that was made, explain how they use the inputs of various group members, and if not, why, and how they used the varying arguments and information to reach the ultimate decision. Let's review one more time why a fair process is so important. It serves two critical roles, to promote shared understanding among team members and to obtain a commitment for the course of action going forward. Research in this area called procedural justice strongly supports the notion that people are more likely to go along with the decision and to implement it, even if they disagree with the conclusion if they feel that the process is fair. In short, without commitment and buy-in, decisions are really just statements of wishful thinking. Employees don't have to agree with every decision, but they do need to understand their rationale and accept the process as fair. Effective implementation requires balancing generating constructive conflict while ensuring consideration for dissenting points of view.

Closure: Eventually, a decision-making process needs to come to a closure. The team needs to converge on a solution that it believes is most likely to generate the desired outcome. Consensus on what is the best option available does not necessarily suggest it is accepted with equal enthusiasm by all team members. It is not uncommon for team members to prefer a different option. Many teams don’t want to confront the discomfort associated with disagreement. That often manifests itself in terms of the time consumed by the process. Groups can move to closure too quickly in order to gloss over disagreements. Similarly, the process can consume far too much time, because the group is unwilling to confront that there is no answer that is fully acceptable to all parties.

Interestingly, both premature closure and delayed closure are often the results of zealous advocacy—but from different sources. Why do groups decide too early? As we saw with JFK’s team, people’s desire to be considered team players outweighs their willingness to engage in critical thinking and thoughtful analysis. Groupthink sets in. Advocates of the chosen course of action become increasingly confident and assertive, dissent disappears, and the group prematurely settles on the favored answer.

Why do groups decide too late? Often, it’s the desire for evenhanded, unlimited participation. Team members refuse to compromise, resulting in gridlock. Even after the end of the official discussion, different factions reiterate their positions in one-on-one conversations. The leader thinks the issue is settled, but the argument is still burning underground, like roots when a campfire hasn’t been put out properly.

What can leaders do to strive for timely closure? Once again, the answer comes down to mindset and method. When a group is deciding too early, what's required are leaders who are able to recognize nonparticipation and unstated dissatisfaction, changing the mindset of team members by encouraging diverse perspectives? Alfred Sloan who ran General Motors for decades during its early glory years was really good at this. He once said to his senior team, "I take it that we're all in complete agreement on the decision here. Then I propose that we postpone further discussion of the matter until our next meeting to give ourselves time to develop disagreement and perhaps gain some understanding of what the decision is all about." Conflict-based decision-making methods like dialectical inquiry and devil's advocacy are equally powerful in bringing forth minority views by the structure of debate and explicit rules that require a multiplicity of views.

What about deciding too late? In this scenario, what's required are leaders who are able to recognize the diminishing returns from collecting additional information, comfortable calling the question with limited data, and then signaling with forcefulness that debate is now over, and it's time to move on. Two good techniques for preventing late closure are our default to the leader, and the two hats.

The first approach, which has been found among rapid decision-makers in Silicon Valley is acceptance of a simple rule. Teams will strive for consensus, but if it can't be reached, all members of the team agree that the leader will make the call and that her decision is final. Second, and a favorite of mine, is the two hats dynamic —made famous by former Corning's CEO Jamie Houghton. When debating topics with his senior team, Houghton would tell the group that he was wearing one of two hats — a cowboy hat to signal that he was mixing it up and open to debate with members of his senior management team or a bowler the formal British hat, indicating that he was calling the question, making a decision, and was no longer willing to entertain endlessly advocacy and further discussion.

Achieving closure is a function of creating a process that builds sufficient alignment within the group to allow that group to move forward. It should be clear by now that alignment is not synonymous with universal agreement. Any decision-making process that is designed without considering the variable of time is vulnerable to failing. In designing a decision-making process, general managers consciously select a process that will allow for creative conflict, ensure consideration of alternative views, and come to closure in a time consistent with the organization’s objectives.

JFK, Take II: Decision-Making Done Right

Fall of 1962 — there are huge tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States, largely because of military shipments from the Soviet Union to Cuba. Robert Kennedy, the US attorney general, and brother to the president has a meeting with the ambassador from the Soviet Union, who assures him of the Soviet Union's intent. There will be no surface-to-surface missiles placed in Cuba. Senior US officials are suspicious. They draft a formal statement saying if such a step was ever taken, there would be serious repercussions. October 16, 1962 — the president is informed that intelligence photos show that the Soviet Union has sent not only missiles but atomic warheads to Cuba. The reaction of the cabinet group that reviews the photos is a stunned surprise. They had absolutely no expectation that this would happen. The group that meets on October 16 continues to meet for 13 days. We'll focus on the first five days when much of the critical decision-making was taking place. Day one — the meetings begin, and the general reaction is we have to do something. Now the immediate reaction is to proceed with a surgical airstrike. The US will take out the missiles on Cuban soil. But at the end of day one, a second option emerges-- a blockade or a quarantine. The US will not allow Soviet supply ships to go to Cuba, even though some missiles are already there. Day one ends with these two options on the table. On day three, they begin to flesh out the options. And the majority favors the blockade. Meanwhile, the group has been working without the personal presence of President Kennedy. Why? Because it's an election year, because he has other commitments, because they don't want to arouse suspicions from the public, from Cuba, or from the Soviet Union, and because they learned an important lesson from the Bay of Pigs. That team members will play to the president, that his mere presence will limit creative thinking.

Late in the evening of the third day, the group briefed the president. They come in with a plan favoring a blockade, but then people's minds start to change. The president asks tough questions and is thoroughly dissatisfied with the answers — think here of Alfred Sloan in his approach to the decision-making at GM-- he sends the group back to work. Compare the level of critical thinking here to the level that occurred in the Bay of Pigs. What was the likely impact of the President’s tough questions after hearing the details of the proposed recommendation?

Day four, the group works out a plan for coming up with two clearly defined options. First, they break the team into two subgroups. One group focuses on the surgical airstrike. It develops the president's speech and all the actions necessary to support that approach. The other group focuses on the blockade, and develops a similar speech and set of actions. The subgroups work all morning, and then what do they do? They switch position papers in order to critique, refine, and improve the other's plan. And then what? They trade position papers again, back to the original developers, and try to respond to each other's concerns. By the end of day four, they have two fully fleshed-out options. Throughout their discussions, they've also been working with a very distinct set of norms. First, there's no clear single leader. They rotate leadership responsibility because the president is not always present or in the room. Second, the rules of protocol and hierarchy are suspended. They speak as equals, following the suggestion of the president that they take on a very distinctive role in this decision-making process, not representing their departments, but acting instead as skeptical generalists, looking for the general welfare and asking hard questions about each other's proposals.

Kennedy's advisors used a mixture and a modification of dialectical inquiry and devil's advocacy. Elements of dialectical inquiry include the two subgroups developing differing plans and critiquing each other's arguments. Elements of devil's advocacy include each subgroup's critiquing the other's plan, but also the charge to individual team members to act as "skeptical generalists.” These approaches encouraged all members to voice their ideas and concerns and helped prevent the groupthink that undermined decision-making during the Bay of Pigs. Kennedy's advisors did not split into subgroups until the fourth day. Do you think this timing was good or should they have done it earlier—or later? Why? There are subtle but important risks to forming subgroups too early. If they are created right from the start, there is a tendency to identify with one’s subgroup and advocate for its approach. Had Kennedy’s cabinet divided into blockade and bombing subgroups right from the start, it would probably have been far harder for them to remain open to each other’s viewpoints and to develop a sense of shared ownership and commitment to both recommendations.

Making the Call: After a long meeting, the President makes a decision on the blockade. He sends the group to work. Day 5—the teams tell the President that they are ready to present. He meets with the entire team and hears both options presented in full—surgical airstrike and blockade. After an intense, multi-hour meeting, he decides in favor of a blockade. What did Kennedy gain by waiting an extra two days after the first group presentation? Compare this with the Bay of Pigs decision. Under such time pressure, leaders play an especially important role. They are usually the ones who must “call the question.” Here, JFK’s approach matched the advice of Richard P. Simmons, for many years the highly successful CEO of Allegheny Ludlum Steel Corporation: “What we’re trying to do is keep our options open as long as possible. So you start with management rule number one: don’t make a decision before you have to make it, but then don’t make it after you should have made it. There is an appropriate time at which a strategic decision has to be made and that’s what people like me get paid to do.”

Case study: Decision-making on Mt. Everest, 1996

In May 1996, 23 people reached the top of Mount Everest, the tallest mountain on Earth. Among this group of climbers were Rob Hall and Scott Fischer, two of the world’s top mountaineers and guides. But both leaders, along with three of Hall’s paying clients, died during an unexpected storm as they headed back down later in the day than they had planned. Other climbers in from Hall and Fischer’s two expeditions spent hours descending in subzero temperatures and fierce winds, barely making it out alive. It was the deadliest climb in the mountain’s history. Many surviving climbers and observers have tried to figure out why the tragedy occurred and, in particular, why several climbers, including both leaders, continued on to the top despite the dangerous conditions that day.

The time, May 11th, 1996. The place, Mount Everest, the highest mountain on Earth. A young oxygen-deprived leader from New Zealand sits just below the summit. He reports to base camp that one of his clients and friends, Doug Hansen, has just died. The leader's name is Rob Hall. He's an expert mountaineer who has summited Everest before. And after months of arduous training with his team, he's back again. But the agony of training doesn't compare to what he faces now. Because of a flawed decision, his team is now in perilous straits. And he knows the consequences. Had he turned around at 2:00 PM, as was his custom, to avoid descending at night, he and his team would, in all likelihood, now be safe at base camp. But he and most team members pressed forward instead. Hall struggles for hours to reach the South summit, where he's finally able to breathe supplemental oxygen. At this point, however, it does him little good. Every part of his body aches. And the storms ahead will not allow him to proceed. How and why did things go so wrong? Was Hall simply overconfident, too convinced of his leadership skills and the capabilities of his team? Should he have allowed the members of his team, especially the guides with more extensive climbing experience, to speak up and be more vocal? Would he be in the situation if they had expressed dissent? Or maybe it was his commitment to helping Doug Hansen reach the summit that did him in, a commitment that created a sense of personal obligation. As night falls on May 11, Paul uses his radio to call base camp. He finds out that along with Hansen, three other climbers from another team, including its leader Scott Fischer, a friendly rival of Hall's, have also perished. Hall asks base camp to speak to his wife for one last time. They are able to patch her through. And Hall says, honey, I love you. Sleep well, my sweetheart. Please, don't worry too much. No one ever heard from Rob Hall again. This table provides a snapshot of the members of both of the 1996 climbing teams led by Hall and Fischer, respectively.

*=died during the descent from Everest

What was it that led to such tragic outcomes on Everest? I'd argue there was no single root cause. This is actually a common finding for managers when examining major failures in flawed decisions. When plans, projects, or journeys go off track, there are usually multiple causes. As Anatoli Boukreev, one of the surviving guides, writes, “to cite a specific cause to an event would be to promote an omniscience that only gods, drunks, politicians, and dramatic writers can claim.”

So if anyone says they have the single explanation or the sole answer to something, they are, at least in my experience, trying to sell you something. The true story behind poor decision-making is usually far more complicated. In the case of Everest, the events of 1996 can best be understood by using three levels of analysis – the individual level, the group level, and the organizational level. Each level brings its own unique perspective. But at the same time, each reinforces and interrelates with explanations from other levels. These explanations aren't mutually exclusive. They're complementary. In this analysis, we'll look at several explanations, at these three levels, that may have contributed to the tragedy. From a process perspective, any decision can be viewed as the outcome of forces working at multiple levels, many of which managers have at least some control over. For this case on Everest, one can focus on factors that occurred at the individual level (factors that influenced the judgment of individual climbers) and on the group level (adverse team dynamics that prevented concerned climbers from speaking up). As we’ll see, both factors were caused by poor processes.

Cognitive Biases: The Everest story provides examples of cognitive biases that can befall not only mountaineers but also managers. A cognitive bias is a systematic error in judgment that occurs because of the way our minds work. For example, if you’ve ever said to yourself, “I knew I shouldn’t have made that hire. I had mixed feelings about him all along,” you’ve fallen victim to what psychologists call “hindsight bias.” That’s our tendency to look back and see the outcome of an event as having been predictable at the time. In reality, there was no way you could have “known” the candidate would not work out, but in retrospect, you only remember the red flags and discount the reasons you had for hiring him.

Overconfidence: Many cognitive biases can impact managerial decision-making. For example, much research has shown that people from a wide variety of professions tend to exhibit overconfidence in their choices. A combination of past successes and big egos produces an inflated sense of one’s own ability. One underestimates—or flat-out dismisses—the possibility of failure. Rob Hall and Scott Fischer, the team leaders on the Everest climb, provide a case in point. Both were skilled, accomplished climbers with much to be confident about. On this particular climb, however, self-confidence may have led them to make poor decisions. Hall, in particular, had an amazing record of success on Everest. This may have given him a feeling of invincibility that ultimately did him in. As one of his clients later explained, “Hall believed a major disaster would happen on the mountain that year. However, his feeling was that it wouldn’t be him. He was worried about having to save another team’s ass.” Scott Fischer was even more optimistic. When questioned about the inexperience of his team, he responded: “Experience is overrated. It’s not the altitude that’s important, it’s your attitude…We’ve got the Big E completely figured out. We’ve got it totally wired. These days, I’m telling you, we’ve built a yellow brick road to the summit.” Fischer also told a journalist: “I believe 100 percent that I’m coming back…My wife…isn’t concerned about me at all when I’m guiding because I’m [going to] make all the right choices.” It wasn’t just the leaders. Many of their clients were equally overconfident, despite their lack of high-altitude experience. As Jon Krakauer put it, most of the clients were “clinically delusional” when it came to judging their own abilities. For example, Beck Weathers, one of the doctors on Hall’s team with little climbing experience, said: “Assuming you’re reasonably fit and have some disposable income, I think the biggest obstacle is probably taking time off your job and leaving your family for two months.”

Consideration of Sunk Costs: Another mistake made by some climbers was their failure to disregard sunk costs. Sunk costs are investments in time, energy, money, or other resources that can no longer be recovered. When considering potential courses of action, such as whether to continue climbing a dangerous mountain, one should disregard such costs because no matter what you decide, you can’t recover what you’ve already invested. Nonetheless, research in behavioral economics and other fields has found that individuals, teams, and companies often do include sunk costs in their calculations. Why? Because we just can’t bear to “give up” all of the time, money, effort, and resources we’ve already put into something. So we stick it out. Often, people will even escalate their commitment to a course of action, thus losing even more. This is known as “throwing good money after bad.” We do this because of another cognitive bias: we are loss-averse. That is, we cannot bear to admit to ourselves that we made a wrong decision. We would rather take a gamble than accept a sure loss. In a life-or-death situation, however, these tendencies can do us in.

Managerial Tools for Combating Cognitive Biases: How can managers guard themselves against these biases when making a high-stakes decision? Here are a few tips and techniques:

Appoint a trusted team member to be the “de-biaser,” striving to point out faulty thinking and illogical arguments from others.

Create a rule, such as the Two o’Clock Rule, that forces you to put a stop to failing courses of action. To make sure the rule is actually followed, you might empower a neutral party to enforce it.

To avoid overconfidence, take what psychologist Daniel Kahneman calls an “outside view.” Study statistics on the success/failure rate of others who have attempted similar things, such as launching a similar product. Then adjust your own perceived chances of success accordingly.

At this point, you might be thinking, “OK, Hall and Fischer screwed up. But why did everyone else go along with them? Why didn’t the guides or any of the clients put a stop to it?” That brings us to the next level of analysis: the group level. This one won’t be pretty, either.

Adverse Team Dynamics: Besides individual biases that affected the decision to press on during the Everest climb, there were dysfunctional team dynamics that contributed to that decision. In particular, several factors prevented team members from speaking up to Hall, Fischer, and the other guides, even though many climbers felt repeatedly that the group should have turned around. With their own lives on the line, what do you think kept the clients from speaking up when they felt they should have turned around?

Psychological Safety: Team members likely didn’t speak up because of the many risks of doing so: the risk of being seen as a coward, the risk of being criticized by the rest of the group, and other social risks. In the words of Harvard Business School Professor Amy Edmondson, team members probably did not feel as if they were in a “psychologically safe” environment. According to her research, psychological safety is the “shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking.” In psychologically safe environments, team members have a lot of trust and respect for one another. They’re not worried that the group will penalize them for speaking up or challenging the majority opinion.

Psychological safety is a belief that I can be myself at work, that I can ask questions, that I can raise concerns, that I can point to mistakes and failures, that I can get help if I need it. So I'm not tied up in knots worrying about what people think of me. Psychological safety is experienced by individuals, but it tends to be a group-level phenomenon. You will find remarkably similar assessments of the psychological safety among people who work closely together in some workgroup or some interdependent unit in the organization. And so, for example, in a hospital, that might mean that one patient care unit has a high level of psychological safety, while the patient care unit across the hall has a low level of psychological safety. That tends to be related to how the local leaders behave in those different units. I have never seen an organization that is uniform in its level of psychological safety throughout the organization. So it neither is something that individuals hold and bring to the organization themselves nor something that is entirely driven by the organization's culture. It's something that very much takes shape at the workgroup level among inter-dependent people who are getting some shared goal accomplished.

If I'm in a psychologically unsafe workplace, I’m second-guessing myself all the time. I'm thinking, hmm, I'd like to say that, but maybe she won't like that, so I'm not going to say that. Or I really wish I could raise this concern, but I don't know that that would be accepted here, so I don't. So I'm holding back. In a psychologically safe workplace, I'm not holding back. Psychologically safe groups are more likely to be effective and make better decisions. Why? Because people surface more important information during discussions and aren’t afraid to challenge one another or point out faulty assumptions. When members of a work team (or a climbing team) feel as if they can’t speak up, however, the decisions that the team makes are more likely to turn out poorly.

Factors that Diminish Psychological Safety

Perceived Status Differences: Several conditions likely undermined psychological safety in the teams led by Hall and Fisher. One was perceived status differences. For example, when descending the mountain, Andy Harris, one of the guides, became disoriented from the severe conditions, but because he was the guide, clients failed to question if he needed help. Jon Krakauer later regretted that: “My ability to discern the obvious was exacerbated to some degree by the guide-client protocol… we had been specifically indoctrinated not to question our guides’ judgment. The thought never entered my mind…that a guide might urgently need help from me.” But it wasn’t just clients. Guides themselves felt pressure to go along with the decisions of Hall, Fischer, and more senior guides. There was a pecking order, with different guides being paid differently. As Neil Beidleman, a surviving guide, noted, “I was definitely considered the third guide…so I tried not to be pushy. As a consequence, I didn’t always speak up when maybe I should have.” Unsurprisingly, status differences often play a major role in organizational decision-making. All too often, the highest-ranking person makes the decision, despite the actual merits of his or her idea. Others don’t want to “step on anyone’s toes.” As we’ve discussed, decision-making is a process, and managers can influence processes to improve them. How can managers prevent status differences from creating this adverse dynamic?

Leadership Style: Another factor that helps determine the level of psychological safety in a group is leadership style. For example, will the leader entertain questions from team members? Are they open to dissenting views and ideas? Are they willing to listen to members’ valid concerns about a course of action? On Everest, both Hall and Fischer were not. Before the final climb to the Summit, for instance, Hall told his team: “I will tolerate no dissension up there. My word will be absolute law, beyond appeal. If you don’t like a particular decision I make, I’d be happy to discuss it with you afterward, not while we’re up on the hill.” This may have made sense given Hall’s expertise and the possible need for quick life-or-death decisions, but it certainly suppressed people’s willingness to question his judgment when he decided to ignore his Turnaround Rule. As one client put it, “passivity . . . had been encouraged throughout the expedition.”

Team Familiarity: Another impediment to psychological safety is team members’ unfamiliarity with one another. In the case of Everest, most members of the two climbing teams had never met each other before and the tight schedule left little time for them to get to know one another and develop the trust and mutual respect necessary to speak up and express doubts. As one client put it, “One climber’s actions can affect the welfare of the entire team…But trust in one’s partners is a luxury denied to those who sign on as clients on a guided ascent… [we were] a team in name only.” As a result, even when teammates were concerned about one another, they would not always speak up. As Anatoli Boukreev, one of Fischer’s guides, put it, “I tried not to be too argumentative, choosing instead to downplay my intuitions…I had been hired to prepare the mountain for the people instead of the other way around.” Despite his concern about the skill level of the climbers, Boukreev didn’t feel comfortable voicing his concerns.

Managerial Tools for Increasing Psychological Safety: In all, perceived status differences, autocratic leadership, and unfamiliarity between team members served to diminish psychological safety on Everest and create an atmosphere in which people were not comfortable speaking up. The result? Climbers failed to question the (questionable) decision to keep going.

With this in mind, what can a manager do to create psychological safety in a decision-making group? Here are a few techniques:

Reduce perceived status differences on your team by admitting to others your own fallibility as a manager (and a human being). This will encourage others to do the same and make it safe for them to contribute their ideas to the conversation.

Make sure that everyone on the team knows his or her ideas and opinions are valued (even if it their ideas are not used in the end). To get people engaged, you might ask open-ended questions that invite participation and make it a point of to draw more junior (and likely quieter) individuals into the conversation.

Have the group meet informally to get to know each other before a big decision must be made. If this is not possible, use the first ten minutes of a meeting to allow people the chance to get to know one another.

At this point, it seems that some of the mistakes made on the Everest climb could have been avoided by making key managerial process choices to reduce the impact of cognitive biases and to increase psychological safety. In other words, the mistakes made on the Everest climb could have been avoided with a tighter focus on the process.

Learnings from Mt. Everest

We’ve now been through the two levels of analysis. Let’s recount the lessons learned. Let's now take the big picture view, what we call the view from the balcony. The Everest case gives us a window into an essential skill of managers - effective decision making. What can we learn about decision-making from the 1996 tragedy on Everest? Here are four essential lessons that the case raises for me. There are undoubtedly many others.

First is the importance of being open to multiple explanations of decision-making failures. When disasters like that on Everest happen, or projects or strategic initiatives fail, it's all too easy to engage in an elusive search for the single determinant or culprit. Silver bullet theories or finger-pointing are all too often the norms in many businesses. Yet in complex systems with many moving parts, single explanations are frequently too simple to help us learn from mistakes and make better decisions next time. Instead, you almost always benefit from hearing multiple explanations for an organizational issue and piecing them together to arrive at a deeper understanding of a particular problem.

Second is the danger of stifling constructive disagreement or dissent. When teams operate in an environment of psychological safety, they tend to express more dissenting views, which improves the quality of decisions made. This is a concept that we'll come back to again and again in the course. In Everest, several conditions, most notably the management styles of Hall and Fischer, decreased the likelihood that team members would speak up. And the results were tragic.

The third is the importance of learning from failures, a topic we devote much attention to later in the course. Often we attribute the failures of others to character flaws or to bad decisions. I'm sure many of you thought that Hall and Fischer were overconfident and that in their shoes, you wouldn't have made the same mistakes. By engaging in this kind of thinking, however, we delude ourselves into believing that things will be different for us. And this leads us up the same mountain as Hall and Fischer with likely the same results.

Last, but not least, is the importance of recognizing that it takes different skills to manage and lead teams and groups than it does to perform as an individual. Managing a team requires a distinctive set of skills, often not mastered during people's tenure as individual performers. Such skills include designing and directing team decision-making processes, a topic we will cover in-depth in the next module.

In short, Everest shows that the inability to shape an effective decision-making process is a severe managerial handicap.

Key Decision-making Principles Held by Maplerivertree

After this length discussion, we provide three principles Maplerivertree believes in.