Negotiation

One of Maplerivertree’s goals has been to advise clients on how they can negotiate more effectively for themselves, and for the institutions they represent. Enhancing negotiation muscles and routines can have a huge effect on your business or organizations’ success - it helps you or your team make deals that might otherwise slip through your fingers, craft creative solutions that generate added value to the deals that you do settle, and resolve small differences before they escalate into costly disputes. Depending on the negotiation, we will assist you to analyze and develop strategies in the background, or at times jump in and help you steel the conversations.

On the analytical side, in negotiations large and small, we deploy fundamental techniques for calculating your walkaways, identifying the ZOPA (zone(s) of possible agreements), BATNA (best alternative to a negotiated agreement), and managing the process of exchanging offers and counteroffers. Beyond the basics, we explore how value can be generated when there is uncommon ground - when parties have distinctively different preferences, expectations, risk tolerance, or time horizons. We dig into the underlying tension between creating and claiming values. And, when the actual negotiation is underway, we turn our focus to the relational dimension and address interpersonal dynamics, bargaining styles, tactics, and emotions.

ZOPA

The Zone Of Possible Agreements is the range between the most a buyer would be willing to invest and the least a seller would consider an exchange worthwhile, or simply the area where two or multiple parties can possibly find a common ground. ZOPAs do not always exist, and due to bad due diligence or an unkempt negotiation process, one can waste significant time and resources clarifying the ZOPA(s). It is also malleable, even in high-profile cases where parties come well-prepared, the zone can in fact grow, shrink, or disappear. Many negotiation coaches believe ZOPA sets the battleground for the sequential push-and-pull, and that all tactics are effective only in adjusting the size of compromises within a shared ZOPA, but in fact, many strategies (commonly during the early stage of a negotiation) can fundamentally shift your counterparties’ perception of their ZOPA. A few examples include shaping the macro-/or press environment, convincing the parties that a substantive factor was overlooked or newly unearthed, or the introduction of new participants. Before digging into the specifics, if there is one thing to take away from here, is to understand that the aspiration and the expectation you should have before ever getting to the negotiation table is almost as important as whatever you do during one, and thus prepare, prepare, and prepare well.

Fog of War I - in the dark: The full picture of the shared ZOPA is put together piece-by-piece by all parties. Maplerivertree has in the past advised our clients’ lead negotiators to practice silently asking themselves ‘is what I am about to say give away any portion of the known ZOPAs’ every time before they open their mouths. This is not purely trying to be ruthless - the protection of ZOPA can be beneficial for all participants. Once a revelation of the entire ZOPA is made, often as a result of the show of good faith or goodwill, all parties would know exactly where they lie and how far they can push each other. Any suspicion or bluffing falls away. At this point, we can’t know where the outcome of the negotiation will land. One party will always want to go further in one direction within the ZOPA, and the other will want to go in the opposite direction. For this reason, negotiations of this type can be some of the longest and most vigorous. It sounds fair, but we do not want that.

Fog of War II - first or repeated offer: But more commonly, going into a negotiation, you seldom know how big the zone of possible agreement is, or whether there's any room for agreement at all. If you or your lead negotiators have prepared well, you'll have set a provisional walk-away line. That establishes one boundary of the ZOPA. But the other boundary, your counterpart's walk-away, will be obscure at best, just as your walk-away will be uncertain to them. That mutual uncertainty underlies much of the dance of offers and counter-offers that follows. Imagine you are an omniscient observer, watching the process unfold. You know there's actually a ZOPA, but the parties, themselves, are unsure. When someone makes the first offer, one of two things can happen — one possibility is that the offer is outside the zone, for example, a buyer puts out a number that does not meet the seller’s minimum. In that case, since the seller will certainly reject it, neither person has learned anything meaningful about the size of the true ZOPA. Both are equally in the dark.

But that is not the case if the first offer falls within the ZOPA. When that happens, there is a profound shift in bargaining power. Can you see why? In negotiation, information is power, using this scenario as an example - if the buyer’s first offer is more than the seller’s walk-away, the seller now knows something the buyer does not. There will be a deal, or at least there should be. The only question now is where exactly the negotiation will end up. Moreover, the buyer’s generous offer has shrunk the ZOPA to his or her own disadvantage. The seller is not going to say, oh, that’s way more than I expected. Please lower your offer. Maybe the seller will reciprocate the buyer’s generosity by responding with a reasonable counter. But it is also possible that the seller will be emboldened, and quote an even higher price than he or she originally planned. Maplerivertree wants you to feel extremely reluctant to make the first offer. You do not want to give away any part of the ZOPA - and don’t want to display willingness or even the confidence of making a deal. When all parties in the negotiation share this practice, the exchange of offers can sometimes be arduous, as each party tries to locate the other’s walk-away, without giving away any clues about their own. That is ok.

When exchanges of offers start, moving in the fog, concessions can get progressively smaller, as each party attempts to signal to the counterpart that they are pushing him or her close to the walk-away. Some negotiators fall into the trap of bargaining against themselves. They will make an offer, and after getting a response, they will make a better one. Essentially, that teaches counterparts to say nothing and just wait for more concessions. Nevertheless, where there is a ZOPA, parties usually do find their way to an agreement. Each number that is put on the table narrows the gap until parties settle on one that they both accept. Often, though not always, that final number is fairly close to splitting the difference between the first offer and the corresponding counter-offer.

Fog of war III - being bold: Many people understand the above dynamic — at least intuitively. And this knowledge, paradoxically, can drag out negotiations as well. Nobody wants to put themselves in a position where they split the difference between their own reasonable offer and someone else’s ‘ridiculous’ number. So there is an incentive to make bold demands, especially at the outset. Doing so entails a double risk, however. A party that makes a demand that is way out of the ZOPA will have to make a lot of concessions to get down to serious business. Each concession that he or she makes costs that person credibility when they then try to justify their latest numbers. The other risk is more subtle but even more significant: Starting with an extreme number casts the negotiation as a haggle - notions of fairness and reciprocity are likely to get squashed. The process may become a contest of wills (“let me show you who’s the man.”). If neither party is willing to bend, the negotiators may end up deadlocked, even though a deal would leave them both better off. We have seen clients swapping out their frontline negotiators precisely because of this. If you are negotiating on behalf of your business with a potential future partner, or anticipate the negotiation to be cooperative, or rigidly sequential in nature, do keep this in mind.

Enough about the ZOPA - typically when the negotiation is underway, the ZOPA solidifies quickly, and the participating parties start maneuvering within it, and at this point, various offer patterns start to emerge.

Offer Patterns

Let’s take a bird’s eye view of how offers might fly back and forth between a buyer and a seller over the course of a negotiation. The pattern that the offers and counteroffers take in a given case depends on how the parties’ respective strategies interact. Here are some archetypal examples:

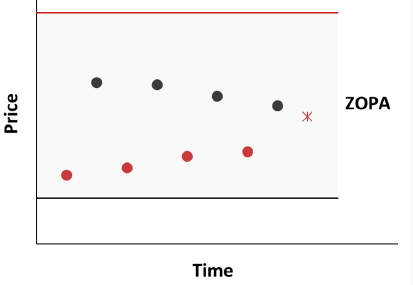

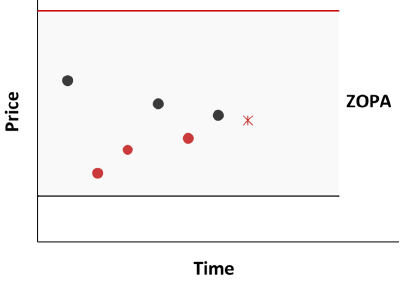

Convergence: Here we see a negotiation where the two parties started some distance apart but made steady progress reaching an agreement. Each concession was echoed by another that was proportionately more or less the same size. The parties came pretty close to splitting the difference between their first two offers (which is often the case), though the seller here came down a little less than the buyer came up. ↓

Stubbornness: The parties reached a deal here, as well, but their story is quite different. In this case, the seller did make concessions along the way, but they were much smaller than those made by the buyer. We are left to wonder whether if the buyer had proceeded more slowly, he or she might have driven down the price. (Then again, maybe if the buyer had been as slow to concede as the seller, the parties wouldn’t have agreed.) ↓

Big concession: This is an interesting contrast to the Stubbornness scenario. Each party moves slowly, perhaps trying to signal their resolve to the other side. In everyday negotiation, it can be hard to tell whether your counterpart doesn’t have much flexibility or whether they are simply bluffing. We get a partial answer in this case when, at the very end, the buyer takes a dramatic jump and accepts the seller's offer. Maybe the buyer sensed that he or she was getting close to the seller's minimum. Maybe time was running out. What the buyer can’t know — and we can’t either — is whether if he or she had waited just a few minutes longer, the seller would have been the one to blink. ↓

Negotiating against oneself: This case differs from the first three we’ve considered in one important way. If you looked carefully, you saw that the buyer made two successive offers, the second one more generous from the prior one. Apparently, the seller enticed the buyer to raise the price without having to make a concession herself. Maybe she just patiently waited for the buyer to bargain against himself. Or maybe she responded to the prior offer by saying, “That’s unacceptable.” If that’s the case, it can be a risky move if it turns out that the number the other party put forth is in fact the best that he or she could do. If you have worked with Maplerivertree, you would know that as a general rule, we never allow this to happen, but always find ways to encourage the other party to do so. ↓

Stalemate: Finally, this pattern shows that the parties did make concessions that were more or less balanced, but in the end, they didn’t make enough of them. (In this particular negotiation, the two parties, both fortune 1000 companies, were only fifteen thousand dollars apart at the end, but apparently, neither was willing to make the final move.) (Note the contrast with the ‘Stubbornness’ scenario, where the seller dropped his or her price at the end to close the deal.) The irony in this scenario is that there was a clear ZOPA here. Each party could have accepted the other’s final offer, but instead, they walked away emptyhanded. Was it a matter of strategic calculation or was there some hostility between the parties? We can’t know just by looking at the numbers that were volleyed back and forth. But we can draw an important lesson: the fact there is room for agreement doesn’t guarantee that the parties will find it. ↓

Counteroffers

One area we try to help clients achieve in is to be completely comfortable in making a counteroffer. This is one of the areas that we've found many times over where even business veterans fall victim to — for the tendency to negotiate against oneself, for which we believe a rule of thumb is to consistently avoid in negotiations. From time to time, we ask our clients to simply repeat “make me a counteroffer (or better offer),” and they go mumbling, “well, make me a counteroffer.” “No,” we would say, “no! say it louder!” And we continue to ask our clients to request invisible counteroffers, louder and louder. If that does not work, here is a real-life anecdote we use to remind everyone that simply asking for a better offer can change everything: once a Tech company found its core team sitting in a technological partner’s headquarter office: the co-founders, CTOs, and head of BDs, silently sweating while waiting, all knew the importance of the renewal at hand - without the tech partner’s technology, their own customer-facing services would dwindle; but at the same time, both parties also knew that the tech company had been building its proprietary substitute, which might come online sometime in the next year. The existing contract cost five million dollars a year, and both parties anticipated the renewal to land somewhere at a slightly lower number. When the negotiation started, a mediator walked into the room and explained that the partner was willing to open at 4.9M, an offer valid by end of the day. Salami slicing, right? So the team sit there and all sort of looked around at each other. In their minds, a goal should be around four million - so how can they get that from an opening of a $100K discount? This is insulting. This is no way to seriously start a negotiation - they said to one another. Felt dejected, while genuinely not knowing what tactics to take, the founder stopped the murmuring, and simply said to the mediator, “why don’t you go back to them and just tell them to start at a lower number.” The mediator said, “no, I do not want to do that,” he continued, “just give me a number, any number; give me a counteroffer, and I will take it back to them, so we can move this forward.” The founder said that they were not saying they were going to leave, but he, the mediator, would have to just walk out and go tell them that we do not like the number. After some additional back-and-forth, while the mediator continued to push for ‘just give me something,” the team kept their cool: “we need them to come back with a better number.” Mediator: “No, this is not how it works. Trust me, I have done this (mediating) hundreds of times. It’s utterly unprofessional folks. I cannot just head back with nothing.” The founder finally said, “please sir, that’s the only way for us to go forward.” The mediator took his papers and walked off to the other room. Once he was gone - he was gone for three long hours, no coffee, no tea. When he came back three hours later, he unfolded his papers and said to the now extremely insecure CTO and the rest of the fatigued members: “they will start at two million.” From that point now, with this slight change in the offer pattern, the entire ZOPA had shifted and unveiled immense intel to the team, making them the driver of the conversation. In the end, this tech company settled the renewal at about one-tenth of the original offer.

Another famous anecdote on ‘irregular offer pattern,’ documented by various leading business schools, is a story about the acquisition of a $7.5M Lichtenstein sculpture. The story is told in the voice of Betsy Broun, the then Director of the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, DC: So one time, a board member came and said, there is a 30-foot tall Lichtenstein sculpture that would look so great at your museum. I'll pay to bring it there and then you can try to raise the money to buy it. My first thought was, gosh, bringing it there is going to be an incidental cost, and buying it is going to be a whopper. I took the idea to the curators. And they immediately saw that this was going to be a big number. It could obliterate all our acquisition funds for one, two, or three years. They saw their own little opportunities drying up because, if we went for this giant big thing, there wouldn't be money for anything else, so they rather universally came out against this idea. Meanwhile, I've got a board member who thinks I'm crazy not for jumping at this. Therefore, we brought the sculpture here, and we installed it. It looked amazingly phenomenal and we all loved it. But gosh, the price turned out to be $5 million. And my curators were frustrated. They could see years of acquisition funds disappearing down the drain. So I went to the owner, a dealer, and I said, we love it, but we can't do $5 million, and I don't have any hope of raising $5 million for this piece, and I'm really sorry. We'd like to keep it on loan for a year but we're not going to be able to buy it. He came back a month later and said, well, I've talked with my partners and we're willing to offer it to you for $4 million. And I said, thank you so much, that's so gracious of you. However, I don't have $4 million, either. And all this unfolds over a matter of weeks. He sooner or later it comes back and says, well, what you could do. And I said, you know, I probably have about $1 million I could put into it now. And if I work really hard and you give me terms, I might be able to come up with a second million over two or three years. Now in truth, I probably could have done more. But I knew I had a reluctant team. I didn't have much backup. I didn't really want to name a higher price and disappoint everyone. So I thought if I could get it for $2 million over a period of years that might be good. He goes away, says, let me think about it. I'll talk to my partners. He comes back later and he said, I have a new price. And I said, OK. I'm thinking maybe he's going to come back with three or three and a half. He said how about free. I said ‘free’ works. How do you get to free? He said, well, I had it appraised. And the appraisal came in not at $5 million, which is what I thought, it came in at $7.5 million. So the dealer can just give it to me and their tax deduction will be worth more than the money I was going to pay. Problem solved. That was probably my favorite negotiation of all time, it was to get a $7.5 million dollar sculpture for free.

Although most negotiations aren’t as dramatic as the above, the takeaway is here that it really does not hurt to (politely) ask people to negotiate against themselves; sometimes you learn something, and other times, you just get lucky.

Tactical Choices

Address easy or hard issues first? Often, at the same time you’re working out the substantive terms of a deal, you’re also implicitly negotiating how to negotiate. Specifically, you’re working out whether the interaction is an exercise in joint problem-solving, or a hardball haggle. You can’t unilaterally decide that question. Whoever sits across the table is likely to have opinions about what the issues are and how to handle them. And people’s approaches to negotiation differ. Some are collaborative. Others are not. It’s always in your interest to elicit constructive behavior if you can. But doing so presents difficult choices. For instance, it’s unrealistic to expect other people to be more cooperative than you are—but being open and flexible may be misread as a sign of weakness. Before committing to one relational approach or another, try to get a good read on the other party. Even when you’re working under a deadline, take some time to establish a positive atmosphere. Don’t jump to conclusions about your counterpart. What looks like hostility might really be defensiveness (or simply a bad day for the other party). Once you both get settled, try making a small concession and see if it is reciprocated. If it is, then you’re most likely headed in the right direction. If not, you may need to express yourself more firmly. There are good arguments either way when it comes to whether you should tackle the hardest issues at the beginning of negotiation or put them off till you’ve made progress on easier ones. But keep two important caveats in mind: First, you may not know which issues are going to be hard and which will be easy until you sit down to negotiate. So be prepared for surprises, pleasant and otherwise. Second, don’t fall into the trap of dealing with one issue at a time. Doing so might seem orderly, but it basically sets up a series of win-lose transactions.

Share or not share? Some people show their cards (information/priorities) in negotiation. But others hold them close to the chest. It’s understandable why some negotiators are reluctant to reveal their priorities. If one person knows the other’s preferences, he or she can both expand the value “pie” and capture most of it. The party in the dark may be left only with crumbs. People understand this intuitively, which explains why many seemingly simple transactions are protracted. If no one reveals preferences, no one gets exploited. But potential value may be squandered, too. Taking the initiative to share information is usually wise. The information certainly does not need to be critical, the other party would not anticipate it either. But a healthy level of dialog can save a lot of time. So always add a note in your playbook to test sharing some information at the onset of the negotiation, but do so carefully, step by step, to encourage reciprocity.

Start high or low? In the “Fog of war III” section, we discussed the downside of making bold demands. Figuring out how much to ask for is like judging your driving speed as you hurry to a meeting. You probably can exceed the posted limit, but not by so much that you’re stopped by the police, given a ticket, and forced to reschedule your appointment. In negotiation, there are two kinds of upper limits. You hit one of them if your demand is taken seriously and the other party walks away. You may try to lure them back, though doing so will make them skeptical about whatever demands you make going forward. Moreover, a bold offer may provoke an equally aggressive counteroffer. Perhaps both sides can back down by making concessions, inch by inch. But that kind of process can drive out value-creation. The punch line? It bears repeating: research suggests that the higher your aspirations, the more you’re likely to get. That’s the good news. The bad news is that you’ll also be more likely to walk away empty-handed.

Raise demands during a negotiation? Raising your demands during a negotiation is straight out of the hard-bargaining playbook. It’s supposed to have two advantages. One, of course, is getting a better outcome on that particular issue. The other is signaling that tomorrow’s terms will be even worse if an agreement isn’t reached today. It’s a high-risk move, though, as it forces the other party to relinquish something that they believed they’d already secured. It also undermines trust. Nevertheless, it’s sometimes appropriate. Let’s say that you’re negotiating a service contract and you’ve provisionally made certain concessions. If another provider subsequently offers more generous terms, you can reasonably ask the first candidate to match—or top—the competing bid.

Last-minute shamefaced and raising demands: Shaking hands on a deal and then saying you have to get your boss’s approval is the classic used-car gambit. In that setting, after the salesperson supposedly confers with the manager, he or she comes back shamefaced and says that you’ll have to pay $1,000 more. The salesperson hastens to add, “But we’ll give you luxury floor mats for free”—as if that somehow makes everything all right. Be careful about using this technique, especially if you have ongoing relationships. People will quickly learn to leave themselves wiggle room, knowing that you’ll come back asking for more. Or worse, they’ll choose to do business with somebody who’s more straightforward. What Maplerivertree generally does recommend is that when you're putting together your negotiating team, remember to leave somebody at home. Because as a negotiating tactic, it's always helpful to be able to say we've got to check with New York, even if you really don't have to check with New York. This allows you to take the sort of pauses in the negotiating. They're often necessary in order to reflect and to regroup. Overall, we think the knowledge or experience in knowing that this trick (last-minute demands) exists is important, but it is always vital to keep in mind that being respectful, being patient, and listening take priority. Let the others play out, share more, and help a win-win to be achieved. In addition, reserve the right to do it yourself, simply because taking the pause at the right time can benefit you. It helps you rebalance (if you were losing it), re-sharpen your focus, and see whether there is a bigger or original picture you are deviating from.

Three quick points to wrap up this section on tactics. Number one, strategy comes first. Your tactical decisions should always depend on whether they advance your larger objectives. Number two, your true bargaining style is expressed in what you do, not by your abstract self-perceptions. And finally, the last point — when it comes to tactics, everything depends on context. As Deepak Malhotra, an esteemed negotiation scholar from Harvard Business School once said, there are no great tactics, only great principles. People often ask Deepak whether it's smart to make the first offer, for example. It depends, is his stock answer. He needs to know about the specific situation. What works in one case could be disastrous in another. And in the end, if you built a spreadsheet with rows listing all the moves and tactics that you might make while negotiating and then constructed columns listing all the contextual factors, you'd go dizzy trying to read it. Focus instead on macro choices. That's Deepak's advice. He calls these great principles. For instance, control the frame, help the other party save face, create value, or foster understanding, and so on. If your specific moves are consistent with such principles, you're likely headed in the right direction. Sounds like excellent advice to us.

Ultimatum(!)

One of the situations we have heard our clients have a difficult time dealing with in negotiations is an ultimatum. So what's an ultimatum? It's an absolute statement of some kind — take it or leave it, do it or else, we will never do this. When ultimatums get thrown around in negotiations, it can make the situation pretty difficult. That's understandable.

Now, Maplerivertree has a pretty simple strategy for dealing with ultimatums. If somebody makes an ultimatum to you — we don't care who made it. We don't care why they made it. We don't care the kinds of things you're negotiating and whether it's face to face or over email or on the phone — if somebody makes an ultimatum to you, your response, almost always, is to simply ignore it. You won't ask people to repeat the ultimatum. You won't ask them to explain it. You are just going to move on to other things. Ok, why would you do that? Well, our thinking goes as follows: A day from now, a month from now, maybe a year from now, there may come a day when what they said they would never do, they might realize they have to do. And what they said they would never do, they actually discover is in their best interest to do. And when that day comes, the last thing you want them to remember is having said 'I will never do this.’ Actually, the very last thing you want them to remember is you remembering them having said ‘I will never do this,’ because, on that day when they're thinking about changing their mind, that's going to be the problem. When you ignore ultimatums, you make it easier for people to back away from those if, and when, the time is appropriate to do so.

There is a risk: what if it's a real ultimatum? What if they really can't do this and there you are ignoring it? Well, at least in our experience in negotiating deals, it's not a real problem. The reason it's not a big problem is that if it's a true ultimatum and if their hands are truly tied, don't worry. They're going to keep repeating it over and over again through every opportunity throughout the process. At some point, based on your understanding of the situation, you can make the judgment that there is really a red line. But just remember, it's often the case that what sounds like an ultimatum isn't a real ultimatum. Sometimes they're just upset. Sometimes they feel like they've been pushed around long enough and now they're going to exert some control. Sometimes they're just trying to get some tactical advantage by making something seem like it's an ultimatum. And for every one of those situations, you're better off, and, in fact, they might be better off, if you've ignored the ultimatum rather than giving it too much attention.

Now, there is a second approach we sometimes lean on if somebody makes an ultimatum. And this is for those situations where it's not really comfortable to ignore what they just said. If the only thing they've said is an ultimatum, it's hard to ignore it and pretend you didn't hear it. So if you are in a situation like that, here's what we'll recommend you do. If somebody says to you something such as “we could never do this,” you might respond by saying, “you know what? I understand, given where things are today, this would be really difficult for you to do. I get that.” Now, what are you doing there? Well, first, you are reframing it and rephrasing it as a non-ultimatum. By saying, given where we are today dot, dot, dot — in other words, tomorrow, or next month, we might be somewhere else. Secondly, you are giving them another out which is to say this is very difficult to do, I understand that, as opposed to acknowledging that it's impossible to do. And both of those make it possible for these folks, when the time is right, and if it's appropriate, to change their mind, to back away from the ultimatum without losing face. The thing to remember is you never want to force people to choose between doing what's smart and doing what helps them save face. And when you ignore ultimatums or rephrase or reframe their ultimatums as non-ultimatums, you make it easier for them not to have to make that difficult choice.

In short, Maplerivertree recommends the following when you face an ‘ultimatum.’

Ignore an ultimatum to give them a future leeway, and give this negotiation and partnership a chance.

People give you an ultimatum for various reasons, most of the time not because there is a true ultimatum.

If it is really an ultimatum, then don’t worry they will keep repeating through every opportunity.

When you cannot get away from giving a response to an ultimatum, say something like: ‘I understand, given where things are today, this would be really difficult for you to do.’ This way it gives the other party enough leeway and acknowledges their challenge.

Remember, an ultimatum does not in any way add value to the outcome for either party in a negotiation.

Creativity | A Roosevelt Story

Till this point, everything we discussed on this page can be categorized under tactics or due diligence. But before we wrap up, it’s important to always add a page to your playbook — as cliché as it may sound — that is always to reserve the room for creativity. There is certainly no SOP for being creative, so we want to simply retell a story for some inspiration:

In 1912, former US President Theodore Roosevelt ran for the White House. Four years prior, in 1908, he decided not to run for a third term out of respect for the two-term precedent that had been set by George Washington, the first president of the United States. But after almost four years out of office, Roosevelt had become tired of private life. He was impatient with his successor, William Howard Taft, even though Taft had been his own vice president, and he had supported Taft in 1908. Now, in 1912, TR remained immensely popular, but he had no political party. Republicans were sticking with the incumbent Taft and Democrats were lining up behind Woodrow Wilson. So Roosevelt invented the Bull Moose Party. Its name and symbol reflected his own temperament. Roosevelt did have enthusiastic supporters. But the newly founded party was largely an amateur outfit. As a result, mistakes were made. As the campaign heated up in the fall of 1912, his staff printed three million flyers that were to be distributed nationwide. They featured a grinning photograph of their candidate. After the flyers arrived at headquarters, somebody belatedly noticed that the photo — and as a result, all of the flyers — contained the words, "Copyright Moffett Studio, Chicago, Illinois." The campaign had failed to secure permission to use the photograph. With Election Day looming, the campaign's options were poor, to say the least. One option was to go ahead and distribute the flyers and hope that Moffett wouldn't know or object. But doing so would be a violation of copyright law. And it would be subject to a fine of $1 per violation, and each flyer would be counted as a violation. More than that, of course, violation of federal law would be both wrong and unwise for a presidential candidate. A second option would be to destroy the flyers and print new ones after getting a photograph from someone else. But that would take time. And time is precious in the dwindling days of a political campaign. So reluctantly, TR's staff decided it would have to negotiate with the Moffett Studio after the fact, in order to get permission to use the photograph it had already appropriated. Given those circumstances, how should Roosevelt's staff handle that negotiation?

Here's what happened. George Perkins, TR's campaign manager, sent a telegram to Moffet Studio. It read as follows: "We're planning to distribute millions of pamphlets with Roosevelt's picture on the cover. It will be great publicity for the studio whose photograph we will use. How much will you pay us to use yours? Respond immediately." Moffet replied that this was highly unusual, but given the publicity, he was willing to pay $250. Perkins cabled back his acceptance without counter-offering incidentally.

So the takeaway for negotiators is this: Just because you have a bad BATNA, don't overlook the possibility that you have something valuable to offer the other party. There are modern-day sequels to this story in the form of product placements in movies. The most famous happened in the early 1980s when producers of Steven Spielberg's E.T. (the Extra-Terrestrial) approached the Mars Candy Company about featuring M&M's in the movie. They wanted the condition that Mars would actively promote their film. Somebody at Mars didn't think it would be worthwhile, so they declined the opportunity. By contrast, the Hershey Company snapped it up. Hershey reportedly agreed to spend $1 million promoting E.T. in ads for its own product. And that's why we see E.T. follow a trail of Reese's Pieces left by Elliott, the young protagonist, not M&M's. Sales of Reese's Pieces skyrocketed soon after E.T. Was released.

Values | Multi-issue Negotiations

Joint surplus: Mutual gain can be generated when negotiators value items differently. The greater the difference, contrary to some conventional wisdom, the more room there is to strike a deal or expand the proverbial pie. Differences in expectations, confidence, or evaluation, are what drive many transactions. The owner of a small company, for example, may think she or he has maxed out its potential and is eager to cash out, but a purchaser looking at the same business may be confident that she has the managerial savvy to make it perform better than ever. That's a case of a pessimistic seller and an optimistic buyer. Closing a deal in such a situation should be easy. Their differing expectations are what makes trade possible. In some cases, however, it’s hard to translate your or others’ intangible expectation or confidence into a number on paper. For example, a vendor is confident that a premium contract that gives him full control will deliver much more saving for the buyer in the long term, while the buyer is on the fence on whether their in-house managerial abilities can be up to the job and thus lower the number on this one transaction. Often, when situations such as this occur, most negotiators end up saving, well, on this particular clause or issue we just have to agree to disagree. But only a few realize the difference in expectations as an opportunity, that can be captured by using tools such as a non-conventional performance clause in the agreements. One might have said something along the lines of “ok, no point about arguing about forecasts, but if I'm right — and I am right — you're going to save this amount of money I'll agree to your terms, but only if I get half the savings as a bonus when I hit the performance target.” It can be hard for the other party to not consider such a demand. After all, all the risk falls on the vendor's shoulders, not the customer's. And if there is a windfall in savings, why not share it? An alternative approach might have been to structure the contingency as a penalty clause, obligating one party to make a partial refund if the service or product didn't work as well as was advertised. From an economic point of view, it doesn't matter whether one uses a bonus or a penalty — a carrot or a stick — though business considerations might argue for one or another in a particular case. One last note in this regard, if you are the party that proposes a performance clause on yourself, try asking for more control in the project pipeline, as granular as possible; by doing so, you are less likely to be hindered in achieving the target and thus collecting your rewards.

Performance clause: Performance clauses are commonly included in agreements that are implemented over a period of time. For example, publishers usually pay authors additional royalties that are contingent on how many copies of their particular books are sold. Likewise, other kinds of contracts may include a penalty clause if a product does not perform as well as was promised. From a purely economic viewpoint, it doesn’t matter whether a performance clause is designed as a bonus or a penalty, you can propose them in a negotiation when a stark difference in expectations, performance, confidence, or evaluation is blocking the conversation. But do remember, think it through before proposing a performance clause - it isn’t a universal cure for deadlocks, it can lengthen the talk as parties bargain over the details, and (in an unexpected way) make you give out a lot more information about your ZOPAs.

The mythical fixed pie: Let’s assess two critical processes in negotiation — the cooperative moves that are necessary to create value jointly, and the competitive moves to claim value individually. And these are often thought of as separate and opposite poles of what one does in negotiation. But Maplerivertree likes to characterize each of them and then show how they interact, and how managing the tension between the cooperative and competitive can result in superior deals. Value creation is the effort to jointly come to a deal that's simultaneously better for both sides, at no cost to either. A really simple example would involve a vegetarian that somehow has a steak dinner, dealing with a carnivore who has a big salad. Obviously, if they swap dinners, they're both much better off, at no cost to either. And this is what we mean by creating value, making both sides better off in a deal. It involves exploring, building trust, communicating, being creative. And that's what we mean by value creation, sometimes referred to as win-win negotiation. Now, value claiming has to do with who gets what share of the pie. Typically, value claiming is associated with old-school win-lose negotiation. To be an effective value claimer — at least according to the classical playbook — you start high, you concede slowly, you dig in your heels, play your cards very, very close to the vest, threaten to walk away, and hope that by doing this, you end up with a better deal at the other side's expense — in other words, a bigger share of the pie. This is one of the most important biases in the area of negotiations Maplerivertree disagrees with. It is what some scholars call the mythical fixed pie. We find that there are experienced negotiators who work with us and learn for the first time that the other side doesn't value the same thing that they value — if one can find out what the other cares about more and what they care about less, the issues can be traded and value can be created. Many negotiators have a tunnel vision of trade-offs between price, delivery terms, financing, personnel, and so on and so forth. One would say: ‘It’s always a zero-sum game - if you don’t see it. then you are simply naïve.’

Well, but let’s just imagine it's Friday evening, and you're going out to dinner and to a movie with your significant other. But you haven't decided where you're going to dinner. And you prefer restaurant A, and he or she prefers restaurant C. And neither one of you likes the suggestion of the other, so you compromise on B. While you're having dinner at restaurant B, you discuss movies. Of course, you want D, and he or she wants F. So you compromise on E. So you have restaurant B, movie E. And then you're driving home from the movie, and it becomes quite clear that you cared much more about the movie choice and he or she cared much more about the restaurant. So CD would have been a package that would have made you both happier than BE. What you've missed is the opportunity to create joint gain by making wise trades across the two issues that you were making that evening.

The point of this trivial story is that creating a joint gain isn't just about creating dollars. It's about creating value by our ability to create wise trades across multiple issues. There are a wide variety of ways that we can create value. The most common of which is this idea of log rolling, or making trades across issues. But we can also make trades across time. We can make trades that involve contingency contracts. The core issue is to identify where one party cares about an issue far more than the other side and craft a wise trade across those issues.

A-priori beliefs: Lastly, when thinking about what the tradeoffs of non-monetary terms are, Maplerivertree recommends that first, you start with what your values are. For instance, what do we want before entering into a transaction? What is our culture? What are our cultural beliefs about transactions? When you start thinking about control, certainly of execution, what you want and like and would expect of a partner, you should have some a-priori beliefs that you might be willing to change, augment, and modify. What’s important is to make sure you've got to come in with them prepared. For example, on the prospect of control, some of our clients have a fundamental belief for their firms that they always want ball control. It's not because they don't trust other people, it's because they have seen a lot of money in that industry wasted by people, who either give in in good times to greed because they think there's a little bit more money to make by hanging on too long, and they don't want to be negotiating with a partner about what the right time to exit is. There are also issues that are non-negotiable because they raise matters of principle or practicality. Others may be a matter of company policy that is beyond one’s control. Know what yours are before entering a negotiation. It not only helps you more firmly push forward in an ambiguous conversation but also provides an opportunity to learn more about yourself as a negotiator.

Emotions

Take a deep breath. When I ask people what they can do in advance of negotiation to put themselves in their ideal emotional state, they're often taken aback. Few of them have ever given much thought to manipulating their own emotions. But they soon come up with some practical suggestions. I've heard students say, it's just like an investor pitch meeting. Don't tense yourself up with last-minute cramming. Give yourself some time to decompress. The same is true in negotiation. The less time you have to get ready, the more important that advice is. Say that you're at your desk, working on your quarterly budget. The phone rings. It's your counterpart in a tough transaction that's dragged on for far too long. Your every impulse might be to leap right into that conversation. It might be smarter though to say, glad you called. Let me wrap something up here, and I'll get back to you in three minutes flat. Then you could lean back, take a deep breath, maybe close your eyes for a moment. Even right now, if you imagine yourself doing that, you may feel how your tension would ease, leaving you better prepared when you do return the call. Other people suggest simple meditation exercises as a way to put aside distracting thoughts. Visualizing may help as well. Imagine yourself having the right balance of calm and alertness. What would that feel like? Or if you sometimes fault yourself for being impatient, think about what it's like to listen without interrupting. If you sometimes are too withdrawn, picture yourself leaning into the conversation and being more expressive. Do what you can to minimize distractions beforehand. When you go to an important meeting, the drive may be easy or traffic may be snarled. Circumstances beyond your command will affect your mood — maybe for the better, maybe for the worse. If it's the latter, bringing that frustration into the room won't be in your interest. Do what you can to put yourself in the proper state. Alright. Let's move forward.

I’m not calm. In some research, we have read that feeling anxious before negotiation can harm performance dramatically. People who feel anxious make low first offers, respond very quickly to counteroffers, make steep concessions, and, ultimately, earn less profit than people who feel calm, neutral, or even excited. Anxiety is bad in negotiations. What can we do about it? So to answer this question, we found out that Harvard Business School has done some research about a counter-intuitive strategy. When most people feel anxious, our intuition is to try and calm down, which is very, very difficult to do. It requires two steps — you have to reduce physiological arousal, these are things like sweaty palms, racing heart, and, not only do you have to reduce physiological arousal, you also have to move from the negative domain, so from the anxiety domain to a positive domain to feel calm. This two-step process is unrealistic to apply effectively every time. Instead of tackling the two-step process, the research’s finding suggests that, well, what if we stay in a high arousal domain? Meaning, instead of trying to calm our nerves, what if we stay high and move from anxiety to excitement? What if we use that racing heart and those sweaty palms and channel that energy in a positive direction? In the study, researchers asked people to do a number of very anxiety-inducing tasks, such as karaoke singing, public speaking, or a very difficult math task — activities that make almost all of us feel very, very nervous. Before participants did them, the researchers asked a simple question, how do you feel right now? And for some of the participants the researchers told them to say, “oh no, I'm anxious.” For some other participants, the researchers told them to try and calm down and say, “oh, I'm trying to calm down.” While for the experimental group, the researchers asked them to say, I'm excited. So how are you feeling right now? I'm anxious. I'm calm. I'm excited. What the researcher found is that just by saying I'm excited out loud, people actually felt more excited. And by feeling more excited, they went on to perform much more strongly on the behavioral tasks. People who said I'm excited went on to sing better in this karaoke lounge that we had set up in our behavior lab. They went on to give more compelling public speeches. And they actually did better on a very difficult math task. So when you're feeling anxious and your intuition tells you to try and calm down, why not just say, no, I'm not going to try and calm down. I'm going to use this energy to my advantage. And I'm going to get excited.

Hot buttons pressed. Knowing your own hot buttons is important, just as important as knowing how to cool them off. You can't control other people's behavior, but you do have a say about how you react to it. And if you're self-aware, you'll be alert to the first internal stirrings of annoyance before that blossoms into full-scale anger. But losing your temper isn't the only way to falter. There are more subtle ways of being off your game as well. If the negotiation is dragging on, maybe you lose your concentration. Your energy may wane. What then? One easy answer is taking a break. It works as a reset button, interrupting whatever dysfunctional pattern has emerged. And remember to take a break before you actually need it so that you're constantly performing at the highest level. We're physical beings, after all. Sometimes, of course, you can't leave the room. But when you're feeling weary or irritated, take a deep breath. It's familiar advice because it works. When you're tense or tired, your respiration slows. That deep breath improves your circulation and does wonder. Without doing anything different physically, you can also break negative cycles by shifting the conversation. If you've been getting nowhere jostling over the details of a deal, talk about broad principles and concerns. Or if you're stuck at that level, see if focusing on process issues jump-starts the interaction. These tactical moves may be useful in themselves as well. More fundamentally, asserting control will help you re-center yourself.

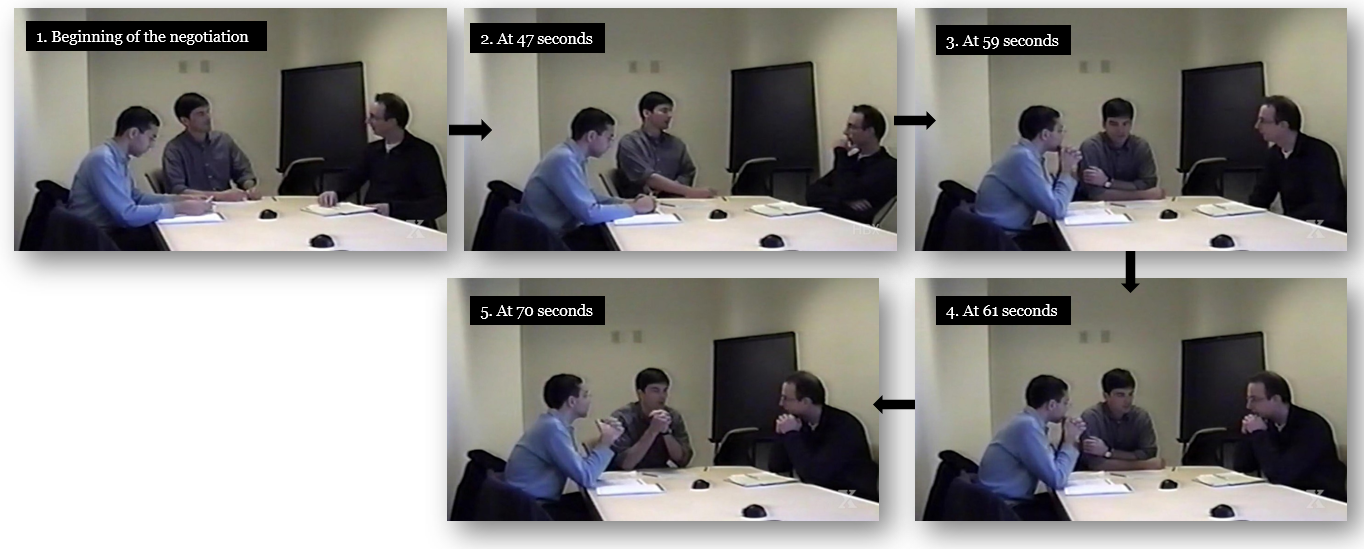

Emotional contagion: Behavior from one person migrates to another, and then to a third. It happens entirely unconsciously, unintended. In recent years, neuroscientists have developed powerful insights about mirror neurons and how they affect how we see and respond to others. The science is fascinating. For us, the takeaway is that behavior and emotions are contagious. What we feel, and sometimes what we do, as a result, is influenced by what others in our company are feeling and doing. Compare these photos of some professional real estate negotiators:

You actually don't need to have heard a word that they said to see that each pair is in sync, though in very different ways. Both parties in the first pair are leaning back, disengaged. In the second pair, the parties are leaning in, attacking the problem, and connected to one another. Experiments have shown that when a fidgety person sits next to someone else, that second person becomes more fidgety too. Likewise, if you have a low and steady pulse and sit next to somebody whose heart is racing, their pulse will slow down.

Here's why that matters in negotiation. If you're centered and calm when you arrive at the bargaining table, your own poise may help others relax a bit. And that's in your interest if they do. By contrast, if you're tightly wired, it will not only undercut your own performance, but your feelings may make others tense up. Three concluding points: First, the important thing about the trio's images is what they reveal about how negotiators relate to one another. The fact that the person on the left had his hand on his chin originally tells us nothing, notwithstanding whatever pop books and body language might claim. But something is going on when they're all doing the same thing at the same time. It's a tendril of connection. Whether it grows into something more substantial remains to be seen. Second, the fact that the researcher spotted the behavior while the three negotiators didn’t doesn't mean that the researcher (or you, who are viewing the pictures) have some sort of social superpower. Far from it. You or the researchers simply had the advantage of not being in the picture. You are not distracted by looking at yourself. Instead, you could take a detached view of how everyone was relating to one another. And that leads to the third point. In the book Getting Past No, author Bill Ury emphasizes the importance of what he calls going to the balcony. Yes, when you're in a big negotiation, you have to be right there on center stage, deeply absorbed at the moment and engaged with your counterpart. But at the same time, you must have the perspective of a member of the audience in the very last row of the balcony, taking in the entire interaction. Maintaining that dual perspective in stressful moments is mentally challenging. And that's when poise is most important.

Anger: We’ve done on-site simulations where we asked the client to actually fake anger for the first 10 minutes of the negotiation. And their roleplaying counterpart doesn't know that their partner is faking anger. So they think that it's real. When we come back into the room, we ultimately come to the takeaway that releasing anger is like pouring out a bucket of poison. It can really create a lot of upset feelings, not only for the person who is expressing anger but for the person who's perceiving it as well. And the person perceiving it has two choices. They can also get angry in response, or they can go to great lengths to try and quell their partner's anger. So we will suggest to most clients that if your partner in the negotiation is expressing anger to you, it is to your great benefit to try and mitigate their anger. And there are a number of ways that you can do this. Number one, if you actually have done something wrong that made them angry, you can apologize. Apologizing is an admission of blame-worthiness. But more importantly, it is an expression of remorse and sympathy. You've realized that they're going through something difficult and that you may have been to blame for it. People are usually reticent to apologize for things. And they shouldn't be. Apologizing is a very powerful conversational tactic. Number two, if your partner seems angry, you might take a moment to step back from the table and let everyone cool off. This can be very, very difficult if you're also feeling angry because anger inspires a fight. But a better response can be “alright, let's take a break, let's step away, and let's sleep on it. Let's think about what we might do better tomorrow.” And when you return to the negotiating table the next day or a week later or a month later, it's likely that those angry feelings will have dissipated and you can have a more productive conversation.

Set a goal on emotion. When we ask clients’ appointed negotiators what they want to feel when they're done, some blurt out, “relieved.” That response says a lot about the stress they must feel while they negotiate. It's understandable, of course. Negotiation is assigned work. It demands concentration, resilience, and creativity in a context where the stakes may be high and outcomes uncertain. But those who feel that negotiation is an ordeal, pay a price twice over. Going into the process, their apprehension makes them defensive and close-minded. And if they're looking at the exit door all the while, they may settle cheaply or walk away empty-handed. With a little more time and a lot more positive emotion, they could do much better. Others answer, “satisfied.” That's what they want to feel. When we probe for what they mean, some clients speak of being satisfied with the outcome all things considered but also feeling satisfied with their own performance. They may have maintained their balance throughout the process. Or if they had a setback, they recovered well enough. Remembering what you want to feel going into negotiation and then taking simple steps to get into that state is well worth it. You'll gain a heightened sense of control and confidence.

To sum up, being prepared emotionally to perform at your best in negotiation, you need to, one, diagnose and address underlying anxieties about the process, two, know your hot buttons, three, have a repertoire of rescue routines to regain your footing if you're thrown off balance. From start to finish, you must be simultaneously calm and alert, patient and proactive, creative and practical.

Wrapping up for now

There is another behemoth of a topic in the field of negotiation: ethics. Every so often in a negotiation, a clear imbalance of information between the two parties emerges, and one finds oneself looking at the opponent walking into a ‘trap.’ Of course - you would say - that’s how it works, but from time to time the ‘trap’ or the line can become blurry. Even the eventual winners can find such situation hard to digest, and ponders at the implications. We are not going to cover this topic on this page (at least now), primarily because ethics isn’t a servicable area for Maplerivertree, but on a high-level we believe that the very best negotiators often end up creating bigger pies than dividing it, and that many modern business negotiations are really just a link in a sequence of collaborations. Thus, try to be a good diplomat, and remember, you don't need to be a moral philosopher to simply be a good responsible person: there are back of the envelope tests that can help you see the right thing to do in most cases. They include, in alphabetical order: The legacy check — is this how you want to be known and remembered? The publicity check — would you be comfortable if your actions were fully and fairly described in the newspaper or online? The reciprocity check — would you want others to treat you this way? The trusted friend check — would you be comfortable telling your best friend, spouse, or children what you're doing? And the universality check — could you recommend that everyone in your situation act this way? If a flag goes up on one of these checks, it's a warning that you may be compromising your principles. If more than one test makes you squirm, change your plans or risk shame and regret. And I always like to remember Mark Twain's advice —"Always do right," he said, "That will gratify some people and astonish the rest."

Lastly, as it is always examined first in an engagement with Maplerivertree, take some time to understand what type of negotiator you are before trying to figure out the opponent - what’s your style? Do you like to take the process relatively slow so you have time to digest and dissect? Or, do you find yourself more skillful when both parties engage in faster dialogs or exchanges? Do you feel comfortable taking pauses in person-to-person conversations, or do you prefer electronic offer exchanges? Are you assertive, or maybe good at dealing with assertive opponents? Having the answers to these self-probing questions can provide you tremendous confidence and setting you up to a great negotiation.

As always, if you have a particular situation you want to talk about, Maplerivertree is one phone call away. ■