General Management

We are all Students of Management

How does your organization structure itself to capture the day-to-day insights that its activities create but often go unnoticed? And how does it benefit from those insights? What did it take to get your organization beyond a vision and a basic strategy to realize its performance objectives? We are all students of management, and often the first to identify the importance of managing processes and people in driving results. Most organizational literature had focused on structure and on topics around compensation and reporting relationships. What Maplerivertree focuses on was that the real role of a general manager was to identify those processes that are fundamental to driving the results an organization is seeking. And the role of the general manager is to structure those processes, get the resources behind them, staff the right people to drive results. If you are building a new business or new functions within the business, what Maplerivertree will do first and foremost is to help you gain insight into what it takes to be the management who can drive results, and who can lead other talents to achieve the type of results your organization is seeking.

The Role of Management

Back to the basics: first, First, let’s ask what it means to be a “manager” or to hire a manager for your business? Just what is “management,” anyway? Those of you who have a lot of management experience may find these questions a bit juvenile, but we see two important reasons to get some terminology straight. For one, the concept of “management” has always been a bit fuzzy. When someone says they are a “manager,” it’s not abundantly clear what they do all day. In fact, we’ve often found that it is managers themselves who have the toughest time describing what it is they do! Why? Because managers often perform so many different tasks from day to day that it’s difficult for them to make sense of how it all fits together. (I would imagine you may feel similarly.) Second, in our experience of analyzing and developing management, we have often found that much of the conventional wisdom about management is plain wrong. As many scholars have noted, there is a large discrepancy between what managers believe they should be doing, what academics think they do, and what they really do.

Management Topology

Fundamental social processes: A manager’s success fundamentally depends upon other people. In that sense, the processes of management are fundamentally social processes. It’s impossible to manage without others. In the broadest sense, Maplerivertree defines management as the art of getting things done through others. Managers normally spend a great deal of time working with and through others to achieve organizational objectives. They are coordinators of people and resources rather than individual performers to drive action. Managers typically establish organizational goals and plans, work with superiors, subordinates, and peers to execute those plans, and monitor progress in a way to carry out those goals. This process of implementation, of ensuring that the job gets done, is the core of management and one that the builder of business and teams should continuously examine. The late Andy Grove, formerly Head of Intel, had a nice take on management. He said that the output of a manager is the output of his or her employees, no more and no less. What does that mean? It means that a manager’s work inevitably involves people, occasionally individuals but more frequently groups and teams, who need to accomplish one or more goals. Managers measure their success by the extent to which the people working for them and with them meet those objectives. As a manager, you're judged by the team's and the department's collective output. Organizations are complex bodies and it's the managements’ job to navigate all the complexity to help individual talents get work done.

In short, Maplerivertree believes that it is most helpful to think of management as an art that can be practiced. Managers practice their art by engaging in various processes—things like planning, budgeting, organizing people, monitoring progress and performance, and others—all aimed at getting things done.

“The word leader and manager inherently sound like an individual, right? There's a person that you think of when you think about the word leadership or the way you think about the word management. But the reality is that embedded in that word is interdependence. A leader is only as good as the work that they can get done through other people. Even management is a job that you have to get done through other people. So while the word tends to put attention on the individual, actually, the most important thing to realize in those words is that you, as an individual, are only as good as the way in which you can work with other people to get things done. So be careful about not thinking of both leadership and management as attributes that an individual has. It's about the things that they do.” – Nitin Nohria, Dean of Harvard Business School

General Management

As a manager (or as a founder who is evaluating your managements’ performance), you will face many challenges, and many of those challenges are often more conceptual and interpersonal than technical. Here’s a shortlist that you may wish to come back to and consider:

Setting the broad direction

Aligning large numbers of people

Integrating diverse perspectives

Getting buy-in from a wide range of stakeholders

Creating a clear and crisp process for decision-making

Ensuring timely, effective implementation of goals

Establishing behavioral and cultural norms

Acquiring and sharing information from a wide variety of sources

These challenges require general managers to develop excellent interpersonal skills—to be well-versed in decision-making, communication, persuasion, negotiation, etc.

General Managers include business unit heads, division leaders, country managers, and CEOs. Their work is representative of the jobs of managers at other levels and provides an especially clear window into the challenges they face. So, what does a general manager do? General management is coordinated action in pursuit of performance. This definition has a few pieces.

First, coordination — managers must coordinate work across many aspects of the business, across functions and departments, across levels of the organization, across business units, and across geographies and cultures. Second, action — general managers are responsible for getting things done, for implementing, and executing. If you are a manager, you not only say you're going to do something, plan it out, and organize people to get it done, you are accountable to follow through and make sure it gets done. And third, performances - managers coordinate actions in pursuit of performance. General Managers have an integrated set of metrics on which they have to score well-- a P&L, a mission, and others. These metrics are integrated in the sense that they present difficult challenges that involve tradeoffs, synthesis, and combinations of inputs to ensure success.

This is general management. But managers at other levels and functions also are responsible for coordinating actions to meet performance objectives. The main differences between types of management lie in the differences in scale, scope, and breadth of the associated tasks. When assigning management roles, one should ask: how much coordination must this manager do? What actions, how many, and how fast, do they have to execute? What performance metrics do they have to pursue and hit?

When an organization, faced with steep managerial challenges, is rethinking its management for specific functional areas, it’s important to consider the challenges through the lens of these three key components (coordination, action, and performance) before determining what tactics to use to solve them. Coordination challenges have different solutions than Performance challenges. Action challenges are often confused with Performance challenges.

The Myths of Management

Juggling these three key components and the tactical choices that compel them across the entirety of your management topology is not an easy task. That’s why you pay full-time positions for your top executives (not a joke). But because it’s difficult, many managers today just don’t do it. They allow the tactical decisions to emerge on their own, rather than making deliberate decisions. Rather than considering the tactical choices as a step in a logical process, they lean on shortcuts and easy answers. This gives rise to management myths.

We all know the management myths—they’re written on inspirational posters or chatted about at the water cooler. We also all know that they’re myths. Yet, despite knowing they’re myths, people still fall into these traps. Why? Often, they don’t answer the questions we just addressed. Achieving each of the key components of management requires designing a deliberate process with lots of tactical choices and implications. People who fail to understand that fall victim to management myths. Let’s hear some common myths.

“The most fundamental myth about management which exists in every undergraduate textbook on managers says managers plan, organize, direct, and control. It's a wonderful way to organize a syllabus, but it reflects in no way what managers actually do on a day-to-day basis.”

“One myth about management that I would definitely like to debunk, is that managers are the ones who have the answers. Nothing could be farther from the truth in today's world. Managers are the ones who have the processes, and have the discipline, and the excitement to engage and empower others who may have better answers than the managers themselves.”

“Well, most of the people I studied became managers because, in fact, they wanted to have more influence. They always thought, if I was the boss, I could do things better. Everybody would be happy, we'd be very productive. Now once they got into the role, they discovered that yeah, you're the boss, but frankly, no one cares that you're the boss. As it turns out, often people don't listen to you even if you are their boss. Formal authority is a very limited source of power.”

“I think there's a tendency for people to look at great bosses and think, I need to be exactly like them in personality, in style, in approach, in values in order to be successful. And the reality is, a huge range of people with much different personalities and approaches to business and life and people can be equally as effective. And I actually think that most of the management is learned over time. Yes, people can have certain char0acteristics that might predispose them to enjoying management more, or to being really talented off the bat at certain aspects of management, but management is an incredibly complex task, and different personalities and approaches can work really well.”

“People somehow have this feeling that there's a boss in the organization, all decisions come from the boss, and everybody else is like a worker bee. I actually think that there is nothing farther from the truth. The further up you go in your organization, the more hesitant you should be to make any decision yourself. This is why processes are so important. You need processes that get other people to gather the information, to make the decision themselves, so that you can enthusiastically support the decision. So a great myth I think is that you're the boss, and being the boss means that you make the decisions. Actually, what being the boss means is you create the context in which others can make decisions that you feel are even better decisions than you would have made yourself. “

By digging deeper into three myths individually, one can gain some familiarity in determining what exactly is wrong with them.

Here’s the first myth: Managers spend most of their time on broad, strategic decisions and long-term planning. Let’s consider this myth from the perspective of the three key components of management.

Coordination: getting people to work together

Action: making sure people actually get the work done

Performance: making sure the work meets key objectives (such as quality, cost, and deadlines)

You could make a strong case that all of them are being missed. The romanticized view of a manager as a dynamic decision-maker and far-sighted planner just isn’t true. In reality, managers spend the majority of their time reviewing, monitoring, and overseeing operations and projects. This usually consists of short interactions, informal meetings and conversations, and a lot of running around to put out small fires. A manager is far more likely to be trying to solve some unexpected operating problems than to be crafting a brilliant long-term strategy.

In fact, managers who do spend more time strategizing, instead of executing, typically don’t last long. As former AlliedSignal CEO Larry Bossidy and management consultant Ram Charan have noted: “When companies fail to deliver on their promises, the most frequent explanation is that the…strategy is wrong. But strategy by itself is not often the cause. Strategies most often fail because they aren’t executed well.”

In many cases, Maplerivertree will focus comparatively less on a client’s strategy (choosing what to do), but more on tangible implementation (figuring out how to do it).

Here’s the second myth: Management involves telling people what to do.

We’re going to look at this from the perspective of tactical choices, using only the abbreviated list most people are familiar with:

Whom do you invite (or not invite) to a meeting?

To whom should you assign a certain task?

How do you delegate to set someone up for success?

How do you lead a post-mortem?

How do you give hard, but fair, feedback?

How do you get buy-in when you want to implement change?

How do you make sure Emma talks to Andrew before he chats with Kelsi?

Looking at this list of tactical choices, what is a better way to describe what managers really do, instead of “telling people what to do?” Coordinating people using the most effective approach to execute the right actions that are aligned in the right timeline to the eventual goal involves rolling the sleeves up and dealing with contingencies. While this might have been the case decades ago, try commanding a designer today to “Be more creative!” or demanding that a computer programmer “Fix bugs faster.” You’re likely to be disappointed by the outcome.

Today, the most successful managers don’t issue commands; instead, they influence the context and environment in which people get work done and create the conditions for people to achieve goals by providing support and making themselves available to solve problems. Today’s manager is closer to a coach or a teacher than to a foreman or a dictator.

Moreover, any effective managers you plan to hire should know that they must manage more than just their own direct reports to get things done. Why? Because organizational action does not occur according to some org chart; instead, it happens through organizational processes—things like product development, logistics, and customer service—that often span multiple levels of the organization and cut across many different departments. (This is also a myth that people think organizational actions occur according to the org-chart. E.g., this is particularly wrong for early ventures.) Being an effective manager means being skilled at influencing people throughout the organization—as well as suppliers, customers, retailers, and other external parties—to get work done. Managing just direct reports simply won’t cut it. That’s why your management topology is so important—your management or you yourself will use these tactical choices in decisions that involve people far outside the direct chain(s).

The third myth is based on a synthesis of problems we’ve just discussed. It relies on the textbook definitions of management, going back to the early parts of the industrial revolution. The classic model of management, first formulated by French businessman Henri Fayol in the early 1900s, included five main functions:

Planning: the manager drafts plans aimed at accomplishing organizational goals, then lays out tasks and schedules, draws up budgets, and allocates resources to accomplish those goals

Organizing: the manager organizes people, assigns roles and responsibilities, and distributes resources to efficiently execute their plan

Commanding: the manager communicates key tasks and responsibilities to employees and directs people in their daily work

Coordinating: the manager coordinates the work of multiple people and groups, and sets up policies and procedures to ensure their plan proceeds smoothly

Controlling: the manager monitors progress and performance and takes corrective action if the plan is headed off track

Since then, management scholars have made some updates to this formulation. For example, “controlling” is often changed to “monitoring” or “problem-solving” to sound more progressive, and “commanding” and “controlling” are often melded into “directing” or “leading.” Regardless of the terms used, however, something like this is specified in every management textbook I’ve come across.

All the above are essential elements of managing. But we’ve found that many managers, especially younger ones, misunderstand them in a way that creates frustration on the job.

First, the five functions above are not tasks to be completed one by one. Instead, they are processes those managers must engage in continually over time. Take a moment and recall - when was the last time you went from start to finish on a project without at least some circling back? A manager simply does not create a plan and then moves on to organize people and never re-visits the plan again to make revisions. (In fact, if they did, they're probably not managing very well).

Second, and relatedly, it is a myth that managers accomplish these functions by taking action. In reality, managers design, refine, and clarify ongoing processes to make sure their subordinates, peers, etc. are aligned to accomplish these tasks. Remember, management is about coordination through others—there’s rarely going to be an item on a manager’s checklist that they can accomplish on their own.

Third, a manager’s job is seldom as neatly defined, pre-programmed, or compartmentalized as this list suggests. Processes often overlap with tasks and activities occurring out of order. Meanwhile, many other necessary processes are occurring—such as negotiating, persuading, motivating, and coaching—that is not on the list at all. The bottom line is that management is messy and being an effective manager means coping gracefully with the mess. That’s why it’s so important, in Maplerivertree’s view, for companies to view the activities of management not as steps but as processes.

Managing vs. Leading

There is a distinction that needs to be made clear which is generally muddy around founders. Great managers and great leaders are different. (Although leader might have more a romantic shine to it.) A manager’s primary job is to ensure the successful execution of a plan through working with people and dealing with complexities. You also often find managers need to pull off fires as it is needed to ensure the execution (sometimes to minimize loss/distraction, and others to amplify wins). There are people in public eyes at a high position are a managerial position and it’s their job to do these.

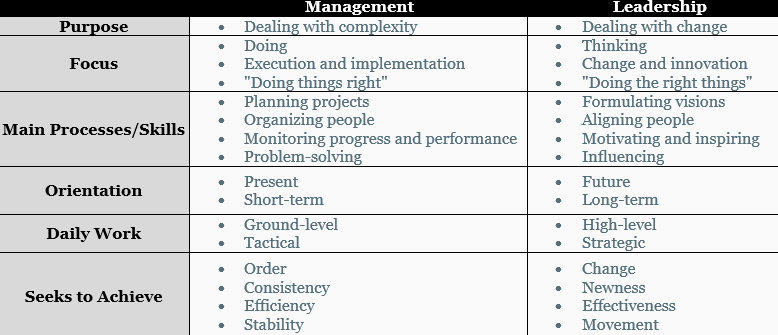

Leaders, especially in today’s world are largely associated with change. It requires quite different a skill set. They are employed, needed, or supported for their ability to bring about change and set the right course for an organization, a country, or a team. Organizations certainly need strong leaders, but they also need managers who know how to get things done—which is something else altogether. So let’s examine how leadership relates to management and the skills central to each. Here are some common perceptions.

“The essential distinction that's made between management and leadership is really very simple. Managers are focused on getting things done. And leaders are focused on making change. “

“Leadership is about dealing with change. And management is about dealing with complexity. John Kotter and Warren Bennis have helped us understand that distinction. And it's a very important one for understanding why it is, for instance, organizations don't change or they get stuck.”

“In my mind, leadership is about setting the vision, using charisma to get people bought in and involved. Management is really the tactical side of that, ensuring that the appropriate processes are put in place, that people are being developed and instructed and held accountable to delivery, and that all of the different functions that are required to meet the end result are coming together in tandem to deliver a final product.”

“I think of management as working with other people to make sure that the goals that an organization has articulated are executed. So, it's the process of working with others to ensure the effective execution of a chosen set of goals. I think leadership is about developing what the goals should be. It’s more about driving change. The two things that are common to both management and leadership are that you do have to work with other people to get things done. But in one case, I think it's with a known set of goals. How do you make sure that you're executing those goals most effectively? That I think of as being management. And leadership I think of as much more about working with people to say what are the worthiest goals for us to pursue. “

“I think there's a real difference between leadership and management. A lot of people debate this. I think leadership is about envisioning the future, and inspiring and leading others to make that future come true. And leadership is often about change, sometimes disruptive change. Management is about making true what, based on the leadership, we've agreed is the plan. I think they're quite different. Great leaders aren't necessarily great managers. Great managers aren't necessarily great leaders. It's rare to find someone who has both skills in abundance.”

Here’s a summary of how these scholars and others have described the difference:

A chart such as the above makes it easy to see why organizations need both management and leadership to endure. With the intensity of competition and pace of change in the world today, organizations must implement in the present, but also innovate for the future. Dealing with change is where good leadership skills really matter.

If you were to take out a piece of paper, write management and leadership side by side, and then list the tasks associated with each you'd find a lot of similarities. For example, both management and leadership involve thinking about strategies. Both involve gaining buy-in from individual workers and groups across multiple levels and functions of the organization. Both involve motivating employees and working toward shared goals. And both require excellent communication skills to achieve those goals. If you look at your list, however, you'll probably notice a broad trend in each column. While many of the tasks and skills are similar, the underlying rationale for engaging in them will be very different.

Leadership is aspirational. It involves persuading the organization and the people within it to achieve specific, and frequently lofty goals. Many of these goals will require the organization and people to change. Management is more tactical. It involves working with employees and providing people with the tools and resources they need to implement today's and tomorrow's goals. Thus, while it's typically said that change is the work of leaders and implementation is the work of managers, that distinction is not quite right. Both management and leadership are crucial to running a business today and making sure that you have one tomorrow.

Maplerivertree focuses on management, and not as much on leadership. Why is that? Well, in our experience in management consulting, we have met many fantastic managers. A few were also great leaders. However, we never met a great leader who wasn't also a great manager. Why? Our own experience suggests that many companies today are neither ‘under-led’, nor over-managed. Rather, I found exactly the opposite. As the scholar Henry Mintzberg puts it, many organizations today are over-led and under-managed (领导有余, 管理不足). That is, there are blessed with great thinkers and visionaries, but lack the practical skills and drive that actually get things done. And that's where the process perspective becomes so essential to success. Why? Because as Steve Case, the former head of AOL put it, "A vision without the ability to execute is probably a hallucination."

Taking a Process Perspective

Every year, countless books and articles are written to teach managers how to be more effective. But many centers on high-level frameworks, looking at businesses from a bird’s eye view. Management is more often at the tree-top view and is a set of processes individuals engage in to coordinate action and to get things done. For most managers, the idea that management is grounded in processes is a subtle, yet powerful, insight.

What are the implications? For one thing, managers must become good at viewing their work in process terms to be effective. They must pay great attention not only to what work gets done but how work gets done—how projects unfold, how decisions get made, how they communicate with others, and so on. In addition, they must find ways to design and structure organizational work to improve how it gets done. In short, they must adopt what I call a process perspective.

What is a Process? Okay, what exactly does that mean? What, for that matter, is a process, anyway? Here are some of opinions and definitions of processes we have heard.

“A process is a set of steps and activities through which work gets done. You can frame a process as an enabling structure, a scaffold, if you will. So the process lets you know how you're going to go about doing it and allows you to use judgment to try something new to make it better. “

“As you go through the process of defining what a process is, you discover it's actually quite simple. It is merely the steps that one must take to get from point A to point B.”

“My definition of a process is a series of interrelated, sequenced interactions that translate ideas into collective organization action. “

“I think a process is anything that gives work structure. And typically, you try to come up with processes that are repeatable and effective in different scenarios.”

To get work done, a manager has three broad organizing tools—high-level strategy, people and other organizational resources, and processes. It's this third item in the managerial toolkit that we have spent a large portion of effort researching. And it's the one that Maplerivertree mostly aims to explore in-depth with our clients on the path to helping them become better-managed organizations.

So, what is a process? In the broadest sense, processes can be thought of as collections of tasks and activities that together, and only together, transform inputs into outputs. Inputs and outputs can be as varied as materials, information, and people. Processes unfold over multiple steps or stages. You can think of the steps in a process almost as links in the chain, from inputs to outputs. Although it's important to note that processes don't have to be linear. In fact, in business, they are often not. Oftentimes, multiple stages can be occurring at once. And earlier stages might be revisited. So what are some examples? Common examples of business processes include new product development, order fulfillment, and customer service. The product development process, for example, is a series of steps that transform ideas and resources into a tangible product for customers. There are many others. These work processes, which aim to accomplish tasks, are quite common. You come across them every day as you do your job.

Process: the DNA of Management

Maplerivertree brings a perspective to our client’s business and helps them dissect the organization as a system of interconnected processes, through which various physical, financial, technological, and human resources are transformed into products, services, and other forms of value.

When many people hear the word “processes,” they typically think of flow charts, manufacturing lines, or the annoying policies and procedures they ought to go through at work to get something done. Processes have the reputation of being rigid, confining, and overly bureaucratic—which is not exactly helpful for getting work done. Some of the skepticism around processes is warranted. And that’s because many companies often get key processes badly wrong. Nonetheless, there are many benefits to processes—if you design them thoughtfully and are willing to re-visit them periodically.

Here are some opinions around the processes we have heard.

“As the leader, when you say, we're going to talk about some of the processes we use, it does not generate a lot of excitement around the table. One myth of process is that they're inflexible. They take too much time and thus they are inefficient. Everything bad about procedures is one of the myths about processes. The second thing is that people say, they're rigid. They won't flex as circumstances flex. That's not true. Great organizations always adjust and readjust processes. Third, people might say, oh, for this thing where we've got to be creative, a process couldn't possibly work. We can't be constrained. Processes are constraining. That doesn't have to be true either. I think the leader who doesn't pay attention to the key processes, their operation, their design, their staffing, and are they working or not is a recipe for doom.”

“One misconception that people have about processes is that they're a straitjacket that they limit or rigidify the work that you have to do, when, in fact, I see it very differently. A process is only as bureaucratic as you let it be. So, you can frame process as something that's rigid, that's keeping you rule-bound and step-bound, and doesn't allow you to be creative, or it doesn't allow you to do your work. Or you can frame-- and I think this is the right way to do it-- you can frame a process as an enabling structure that gives you that starting point, gives you that foundation with which to act, learn, and improve.”

Indeed, processes need not be rigid or constraining; instead, they can be thought of as simple frameworks that managers can use to structure work. Your management should aim to mindfully design processes and then keep re-evaluating them to make sure they are flexible and useful. It may even be useful to remember the distinction between foundational processes - such as decision-making or institutional learning, that underlie almost everything you do, with the more formal, inflexible processes that so often get a bad reputation. And guess what? This is a skill your management teams can learn through practice. In fact, our goal in this course will be to train you to design, direct, and influence various processes to your (and your organization’s) advantage.

Why Take a Process Perspective?

There are several advantages to taking a process perspective to management.

First, by examining processes instead of people or strategies, what Maplerivertree calls using a process lens, managers can better understand how work gets done over time. They will not only understand what work is being done but how it's getting done. The keyword is how. Because processes unfold over time, a process perspective provides a dynamic rather than a static picture of an organization or department at work – a video, not a snapshot, the path for getting from A to Z. And it's in understanding the how of organizational work that managers become more effective. I remember speaking with an accomplished CEO once who said that the primary difference between good and great managers is that great managers know not only what work is being done, but how the work pragmatically gets done in their organizations. They know how things really get accomplished, and therefore, know what levers to pull to make things happen.

Second, the adoption of a process lens forces a manager to be sensitive to the multi-level, multi-functional character of organizational action. All too many managers take a narrow parochial view of organizational work. They tend to look at their functions and levels in isolation and to assume that's where the action is. If I can just do my job and manage my reports, it will all work out OK. Sometimes that's true, but very rarely. On most occasions, managers need to be able to shift their perspectives in order to understand the issues and challenges that they face. This requires skill at making changes in altitude, either going up the organizational ladder to see the larger picture, as it appears to other functions or departments, or down to the ground level to ensure that supporting, nitty-gritty details are aligned and consistent. A process orientation helps immensely in doing so because it provides an intermediate level of analysis that is so often missing, the connective tissue, if you will, that embeds individual actions within the work of the organization.

You can think of a manager having to navigate three levels-- the strategic vision, the 50,000-foot level; policies, processes, and systems, the treetops level, which Maplerivertree also calls the helicopter view; and key tasks and people, ground level. A focus on the treetops, the process level, helps bring together broad strategies with the nitty-gritty details of implementation and brings it to a medium level of analysis. Processes are the glue that holds together top-level organization considerations, and ground-level, individual tasks. This kind of process approach naturally connects you to multiple functions as well.

One last advantage of a process lens is that processes put an emphasis on action and implementation. They provide an element of order and sequence based on actions that must be taken if goals are to be met. That is frequently lacking in managerial work. For many managers, getting things done is all too often a random walk to enlightenment. Processes, by contrast, have a built-in structure. They help to create schema, codes, and routines to help make work easier to do so you don't have to make choices every minute. In short, processes provide a way of structuring the unstructured. How do you think you can influence a process that a team working for you performs? Try to think about how to influence a team that has become ingrained into its routine.

Shaping a Process

One popular view of the manager is that of a visionary, as someone who guides her business unit with creative ideas and grand strategies. Another is the view of the leader, of someone who directs and empowers people, and builds an organizational culture.

But there's another, far less often imagined, but I would argue even more powerful view, that's the manager as a shaper of processes. That is, it's a manager's job to both design and deploy effective processes that can be implemented repeatedly for excellent performance. The question is, how does a manager do this job? What does a manager have in their toolbox to design quality processes to achieve great outcomes? Let's go through a brief example to answer these questions and illustrate what we mean by levers and process choices.

Suppose you are the founder of the company, and as the firm is struggling, you are hiring an effective CEO to help turn the company around. The business had been losing money because of deeply rooted inefficiencies. In particular, its decision-making process is widely viewed as slow, combative, and unproductive. What are some levers or tools that the new CEO will have at her or his disposal to help craft a better decision-making process?

One lever is communication. As the head of the company, the CEO will have a large influence on how key information is exchanged. Is it widely and openly shared, or hoarded and presented selectively, made available in a raw form for the group as a whole to interpret, or pre-processed and filtered?

In a similar fashion, the CEO will have a considerable impact on how alternative ideas are introduced, described, discussed, and evaluated. Depending on past practices and the CEO’s goals, she or he may want a more structured or less structured approach to the discussion.

Here an important lever will be the CEO’s treatment of minority or contrarian views. How accepting will she or he be of wild and crazy ideas?

A second managerial lever is ‘structure,’ in particular group membership and composition. A manager's decision of, say, who to invite to a meeting or who to include on a new project team is often an important determinant of quality processes, decisions, and outcomes. The new CEO will find that seemingly small, insignificant process choices can have a huge impact. Other levers include: 1) The environment in which deliberations take place. What ground rules or norms will govern discussions? What will be the atmosphere in the room? 2) The leader’s own role in the process. Will he or she contribute to the discussion or simply guide it? Strive for consensus or make the call himself or herself? 3) Recruitment.

Continue Reading

To inquire about management consulting services provided by Maplerivertree, contact us. ■